Anisotropic structure and dynamic implications of the upper mantle in the South China Sea

-

摘要: 南海处于欧亚板块、太平洋板块和印度—澳大利亚板块的交会区,是西北太平洋一系列边缘海中最大的边缘海。关于南海的打开以往研究提出了如印度板块与欧亚板块碰撞驱动挤出以及古南海俯冲拖拽等诸多模型。本文力图通过南海海盆及周边各向异性结构来约束南海演化机制。基于同济大学2012和2014年在南海中央海盆进行的两次被动源宽频带海底地震观测试验回收的10台OBS记录仪近1年的地震数据,本文采用三种不同的横波分裂方法,获取了中央海盆针对两次远震的XKS分裂结果以及南海周边20次区域地震提供的S震相分裂结果。SKS分裂结果显示,南海中央海盆下方存在快轴方向为NE-SW向的各向异性,其成因可能与海底扩张时期沿洋脊方向的地幔流以及南海海洋板块俯冲拖拽的地幔流有关。南海及其周边上地幔存在强各向异性,且不同方位观测到的各向异性不同,快轴方向与前人SKS横波分裂结果、GPS和板块运动一致,较好地对应了区域构造运动或者地幔对流模型。各向异性结果与印度—欧亚板块碰撞驱动挤出模型以及古南海俯冲板块拖拽模型预期结果一致,与理想的地幔柱上涌驱动模型不一致。由于海盆各向异性观测特别有限,各向异性结果不能证实亦不能证伪“大西洋型”海底扩张模型、弧后扩张模型和板缘破裂模型,后续还需要更多的观测结果来证实或证伪上述模型。Abstract: The South China Sea (SCS) is located at the intersection of the Eurasian, Pacific, and India-Australia plates. It is the largest marginal sea in a series of marginal seas in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Many models have been proposed for the opening of the SCS, such as the extrusion model driven by the collision of the Indian plate and the Eurasian plate, and the slab pull model related to the subduction of the proto-SCS. This study aims to constrain the models of opening the SCS through the anisotropic structure of the central basin of the SCS and its surroundings. Based on the seismic data recorded by ten ocean bottom seismometers recovered from two passive seismic experiments conducted by Tongji University in the central basin of the SCS in 2012 and 2014, three different shear wave splitting methods are used to obtain the XKS splitting results of the central basin for two global earthquakes and the S phase splitting results provided by 20 regional earthquakes surrounding the SCS. The SKS splitting results demonstrate the presence of strong anisotropy with the NE fast direction in the central basin of the SCS, which may be related to mantle flow along the ocean ridge during seafloor expansion and the mantle flow dragged by the subduction of the proto-SCS plate. Strong anisotropy is also observed in the upper mantle surrounding SCS, and the anisotropy observed in different azimuths is different. The fast directions obtained are consistent with previous SKS-splitting results, GPS, and plate motions, and importantly correspond well to the regional tectonics or mantle convection models. The anisotropic results are consistent with the expected results of the extrusion model driven by the collision of the Indian-Eurasian plate and the slab pull of proto-SCS. The anisotropy results are inconsistent with the ideal upwelling driven model of the mantle plume. Unfortunately, due to the limited splitting observations in the central basin, the anisotropic results cannot confirm or falsify the “Atlantic-type” seafloor spreading model, the backarc spreading model, or the plate-edge rifting model. To verify the above models, further observations are needed.

-

引言

南海处于欧亚板块、太平洋板块和印度—澳大利亚板块的交会区,是西北太平洋一系列边缘海中最大的边缘海,其轮廓呈NE-SW向延展的菱形。由于其特殊的地理位置和复杂的地质构造背景,南海的形成演化动力学机制成为研究西太平洋边缘海演化不可或缺的重要组成部分,同时也在东亚陆缘整体的构造演化历程中有着举足轻重的作用。关于南海的打开以往研究提出了诸多模型:

1) 碰撞驱动挤出模型。当印澳板块与欧亚板块碰撞时,中南半岛开始向SE方向大规模逃逸,南海则沿哀牢山—红河剪切带形成拉分盆地(Tapponnier,Molnar,1976;Tapponnier et al,1982,1986,1990;Briais et al,1993)。但也有研究通过数值计算提出印度次大陆—欧亚大陆碰撞造成的结果是地壳的增厚,而不是沿走滑断层的横向迁移(England,Houseman,1986;England,Molnar,1990)。这种观点也有一些来自观测的证据,如GPS观测到的中国南部WE向和SE向位移只占两个大陆边界总碰撞量的约25%(Shen et al,2000),以及北部湾近海切割红河断裂地震剖面显示的在30—5.5 Ma之间左旋走滑的总量不超过几十千米 (Rangin et al,1995)。而Jiang和Wang (2021)则认为南海在32 Ma打开,远远晚于哀牢山—红河剪切带40 Ma的形成时间,且从东到西的打开方向与碰撞挤出模型预期的从西到东的打开方向相反。

2) 俯冲板块拖拽模型。古南海俯冲到婆罗洲之下时,俯冲板块的拖拽力打开了南中国海。Morley (2002)通过研究走滑断层、裂谷盆地和变质核杂岩,认为婆罗洲西北部的地质演化需要古南海洋壳在始新世到早中新世期间俯冲到婆罗洲之下。Clift等(2008)通过分析横跨巽他大陆架和南海南部破裂边缘(南沙地块)边界的反射地震剖面,认为在大约16 Ma之前南沙地块一直独立于巽他大陆架,而不是碰撞挤出模型预测的属于巽他大陆架,从而推测古南海向婆罗洲的俯冲是南海打开的主要动力。层析成像虽然看到了俯冲下去的古南海板块,然而在地幔深部有相当比例被解释为古南海板块的高速异常位于现今的南海之下,比俯冲板块拖曳模型预期的位置偏北(Wu,Suppe,2018;Jiang,Wang,2021)。

3) “大西洋型”海底扩张模型。基于磁异常条带定年建立的南海扩张模式(Taylor,Hayes,1983;Briais et al,1993),将南海海盆视为一个陆间盆地,以南北被动大陆边缘为界,南海西北及中央海盆在32—17 Ma打开并开始扩张,洋中脊在26—24 Ma向南跃迁,扩张轴从近EW向变为NE向,同时西南次海盆开始扩张,随后中央海盆和西南次海盆在15.5 Ma同时停止扩张。这一模型主要依据有:① 南海磁异常条带的对称性;② 南海海山玄武岩为碱性或介于拉斑玄武岩和碱性玄武岩之间的过渡玄武岩,与弧后盆地的岩石化学特征相比,更接近于主要洋盆扩张中心附近海山的岩石化学特征;③ 南海洋陆边界过渡带具有与其它被动陆缘相似的重力异常;④ 近EW向海山链与预期的扩张中心吻合良好。

4) 弧后扩张模型。Karig (1971) 提出南海的形成与菲律宾海板块向西俯冲后引起的弧后扩张有关。在晚白垩纪到古近纪阶段,西太平洋板块及菲律宾海板块向欧亚板块俯冲,俯冲板块与地幔间摩擦生热,地幔物质熔融上涌,使得地壳拉张减薄,导致菲律宾岛发生弧后扩张而形成南海。在对比南海和日本海已有的地球物理特征之后,Ben-Avraham和Uyeda (1973)认为南海与日本海一样都是弧后扩张形成的,但引发机制有所不同,并基于南海海盆内的近EW向磁异常条带,提出是加里曼丹地块的南迁导致了南海的形成。基于对西太平洋边缘海盆地的基本特征和发育模式的研究,任建业和李思田(2000)认为太平洋板块的俯冲及俯冲带的后撤是弧后盆地发育的主要机制,印度—欧亚大陆的碰撞所形成的向东和东南的地幔流推动东亚大陆东侧和南侧俯冲带的后退,影响和控制了西太平洋边缘海盆地的形态特征及构造演化。

5) 地幔上涌模式。在地幔上涌驱动模型中,地幔上升流导致岩石圈破裂和扩张,从而形成南海海盆(例如,Miyashiro,1986;Wang et al,1995;李思田等,1998;鄢全树,石学法,2007)。Miyashiro (1986)提出的地幔上涌是从澳大利亚附近开始的,并向北最终迁移到南海,形成了包括南海在内的一系列的西太平洋边缘海盆地,并导致这些盆地由南向北逐渐年轻(南斐济盆地除外)。而鄢全树和石学法(2007)则提出促使南海扩张的是海南地幔柱,认为:50—32 Ma时印度次大陆与欧亚大陆的碰撞导致太平洋板块的后撤,为南海提供了一个伸展扩张环境,同时为地幔柱提供了上升的通道;在32—21 Ma地幔柱达到岩石圈底部时发生侧向流动并与地壳薄弱区相互作用,促使南海沿近EW向扩张轴扩张;在21—15.5 Ma,地幔柱效应增强,热点-洋脊作用强烈,扩张轴从EW向变成NE-SW向,触发西南次海盆的扩张;在15.5 Ma,由于巽他陆架与印度—澳大利亚板块碰撞,南海停止扩张。然而,张健等(2001)基于南海地热学、流变学和重力学的结果计算出,南海深部地幔流向是近EW向和SE向的,并不能解释Miyashiro (1986)提出的地幔上涌为什么向北迁移。

6) 板缘破裂模型。板缘破裂模型强调南海东缘走滑断层的影响,认为传统的模型忽视了南海东侧走滑断层的贡献(周蒂等,2002;Huang et al,2019;Wang et al,2019),因为自晚中生代以来华夏古陆岸上及离岸的走滑断层活动,在古近纪以来减薄的欧亚陆壳上发育了雁列式菱形拉伸盆地。花东海盆NW向斜向俯冲以及古南海近NS向俯冲的拖拽力,在欧亚板块与花东地块交界处形成左旋走滑断层,在33—34 Ma (早渐新世)打开了三角形的南海中央海盆。然后,扩张脊向南迁移,于23 Ma在中南—礼乐和红河走滑断裂带之间打开三角形的西南次海盆,而曾经板块边界的走滑断层转换成现在的马尼拉海沟。

7) 复合驱动模型。复合驱动模型则综合各模型利于南海打开以及利于解释观测数据的部分,同时弥补各模型的短板。严格来讲,板缘破裂模型综合考虑了碰撞挤出模型、古南海俯冲拖曳模型,尤其强调了南海东缘走滑断层的影响,也属于复合驱动模型。任建业和李思田(2000)认为,尽管太平洋板块的俯冲及后撤是弧后盆地包括南海发育的主要机制,但由印度次大陆与欧亚大陆碰撞驱动红河断裂右旋走滑和地幔近E向和SE向流动,造成了南海不对称扩张。而谢建华等(2005)通过地球动力学模拟认为,南海的打开和扩张是印度板块与欧亚板块的碰撞、地幔柱上涌以及太平洋板块向欧亚板块的俯冲共同作用的结果。Jiang和Wang (2021) 则认为碰撞挤出、板块拖曳和地幔柱模型依次在南海演化的不同阶段发挥不同的作用,共同推动了南海的打开和发展。

横波分裂作为天然地震观测研究的重要手段之一,在最近的几十年已经被广泛地运用于地壳应力、深部地幔构造变形等方面(例如,Silver,1996;Savage,1999;Crampin,Gao,2006;Long,Silver,2008;Eakin et al,2016)。随着南海构造演化研究的深入,深部地幔流与动力学机制之间的紧密联系日益受到关注。而地幔流难以通过地表地质记录直接观测分析,也难以借助实验验证和恢复重现,利用横波分裂分析是解决该问题的有效手段。由于缺少海底地震仪的观测,只能通过间接的手段推测南海海盆的各向异性,其分辨率还达不到相邻岛弧及大陆地区的程度。本论文基于南海深海区被动源宽频带海底地震仪(ocean bottom seismometer,缩写为OBS)台阵观测试验获取的地震数据,利用横波分裂研究方法,通过分析穿过地幔的横波分裂现象,提取快波的偏振方向和分裂时间,获得地幔的应力/应变方向及强度的信息,并综合前人研究成果以及结合构造地质背景研究南海海盆下的各向异性结构,探究南海海盆经历的动力学过程,为南海演化机制提供约束和线索。

1. 数据和方法

1.1 地震数据

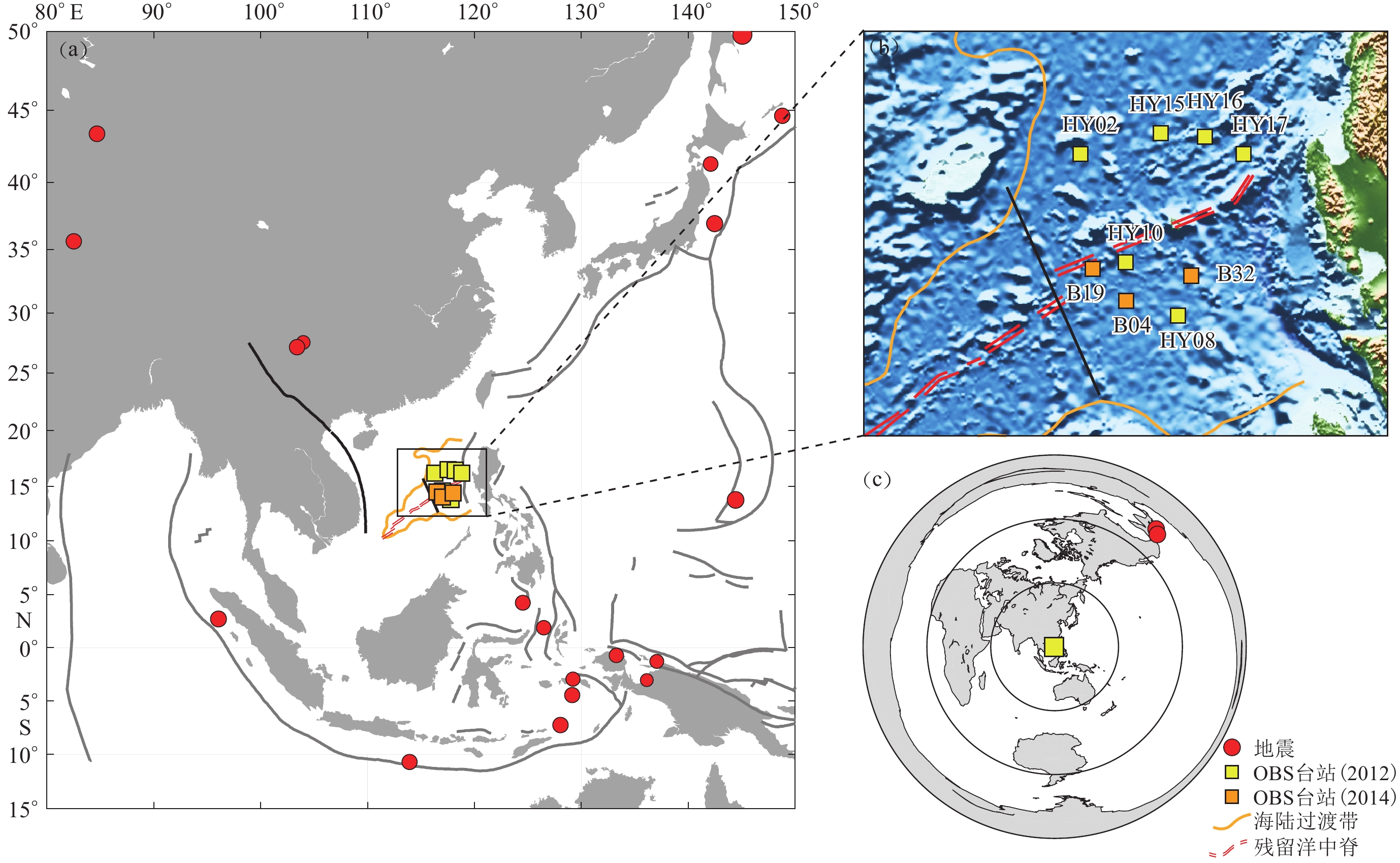

同济大学海洋地球物理与地球动力学组分别于2012和2014年在南海中央海盆进行了两次较大规模的被动源OBS台阵观测实验,两期一共布设了39台OBS,回收了19台OBS (刘晨光等,2014;Hung et al,2021)。通过数据分析与处理,其中10台OBS提供了有效横波分裂数据,这10台OBS的空间分布如图1和图2所示,具体信息列于表1。其中HY01,HY08和HY12以及B04,B19和B32为中科院地质与地球物理研究所研发的I-4C型单大球和双球OBS,其余为英国Guralp公司与法国Azur地学研究所合作开发的Guralp CMG-40T OBS。这两种OBS仪器的频带宽度均为50 Hz—60 s。

表 1 提供有用数据的OBS信息Table 1. The information of OBSs used台站 东经/° 北纬/° 水深/m 记录起止日期 钟漂/s 水平分量方位角/° 倾斜/° 倾斜方向/° (年-月-日—年-月-日) HY02 116.306 1 16.203 3 3 750 2012-04-21—2012-12-03 86.53 20 3.5 160 HY08 117.796 5 13.800 4 4 104 2012-04-22—2012-08-19 0 218 0.7 285 HY10 116.998 3 14.598 9 4 276 2012-04-23—2012-12-09 193.2 166 0.8 215 HY15 117.537 0 16.503 3 3 753 2012-04-25—2012-12-19 0.74 154 16.3 5 HY16 118.213 4 16.451 3 3 920 2012-04-25—2012-12-13 −0.51 26 0.3 91 HY17 118.803 7 16.201 0 3 870 2012-04-25—2012-12-10 −10.54 330 2.0 131 B04 117.011 0 14.024 3 4 246 2014-07-11—2014-11-23 0 185 6.5 280 B19 116.499 0 14.500 6 4 301 2014-07-11—2014-11-23 0 350 6.5 110 B32 117.999 0 14.396 5 3 859 2014-07-13—2014-11-24 0 110 0 N/A 注:台站钟漂的误差在2—3 s之间,水平分量方位角误差约为8°;倾斜指OBS的垂直分量偏离垂向的角度(刘晨光等,2014; Le et al,2018 ;Hung et al,2021 )![]() 图 1 南海区域构造地质、地震台站及历史地震分布图南海的海陆过渡带位置参考Li和Song(2012),马尼拉海沟位置来自Jiang和Wang(2021);其中中南断裂和残留洋中脊的位置来自Zhao 等(2019),红河断裂带来自Yang 等 (2015)。箭头表示板块的绝对运动方向(Gripp,Gordon,2002)Figure 1. Tectonics of South China Sea and the distributions of seismic stations as well as history seismic eventsContinental Ocean Boundaryof South China Sea refers to Li and Song (2012),and the location of Manila trench is from Jiang and Wang (2021). The locations of Zhongnan fault and the remnant mid-ocean ridges are from Zhao et al (2019) and the location of Red River Fault is from Yang et al (2015). Black arrows indicate the absolute plate motions (Gripp,Gordon,2002)

图 1 南海区域构造地质、地震台站及历史地震分布图南海的海陆过渡带位置参考Li和Song(2012),马尼拉海沟位置来自Jiang和Wang(2021);其中中南断裂和残留洋中脊的位置来自Zhao 等(2019),红河断裂带来自Yang 等 (2015)。箭头表示板块的绝对运动方向(Gripp,Gordon,2002)Figure 1. Tectonics of South China Sea and the distributions of seismic stations as well as history seismic eventsContinental Ocean Boundaryof South China Sea refers to Li and Song (2012),and the location of Manila trench is from Jiang and Wang (2021). The locations of Zhongnan fault and the remnant mid-ocean ridges are from Zhao et al (2019) and the location of Red River Fault is from Yang et al (2015). Black arrows indicate the absolute plate motions (Gripp,Gordon,2002)![]() 图 2 (a) 布设的海底地震仪及提供了有用的区域S波震相分裂解的20次区域地震的分布;(b) 中央海盆的地震仪分布;(c) 提供了有用的SKS震相分裂解的两次远震的分布Figure 2. (a) The deployed ocean bottom seismometers and the distribution of regional earthquakes which provide useful regional S-wave splitting results;(b) The enlarged version of the distribution of OBSs in central basin;(c) The distribution of the two global earthquakes which provids useful SKS splitting results

图 2 (a) 布设的海底地震仪及提供了有用的区域S波震相分裂解的20次区域地震的分布;(b) 中央海盆的地震仪分布;(c) 提供了有用的SKS震相分裂解的两次远震的分布Figure 2. (a) The deployed ocean bottom seismometers and the distribution of regional earthquakes which provide useful regional S-wave splitting results;(b) The enlarged version of the distribution of OBSs in central basin;(c) The distribution of the two global earthquakes which provids useful SKS splitting results与陆上地震仪可以准确地确定布放的方位和调平不同,OBS台站从海面投放然后以自由落体的形式到达海底并与未必平整的海底耦合,因而可能存在倾斜且水平分量在海底的实际方位未知。另外由于OBS在海底没有GPS信号,即使OBS的时钟不稳定也不能及时对记录到的地震数据的时钟进行校对,因而地震数据在时间上可能存在较大的钟漂。因此在使用OBS数据前需要对其进行钟漂校正、倾斜校正以及水平方位角校正。本文用来进行上述校正的OBS台站的倾斜角度、倾斜方向、水平分量方位角和钟漂如表1所示。其中OBS钟漂数据参考Le等(2018)和刘晨光等(2014),他们筛选了OBS布设期间记录到的多个高质量天然地震数据,然后针对每个OBS台站比较所有地震的实际P波到时与基于IASP91模型预测的理论到时的差异,并对这些获得的时间差进行统计分析,最后获得了每个台站的钟漂。OBS的倾斜角度和倾斜方向则来自Hung等(2019,2021),他们采用与Bell 等(2015)相同的方法来获取台站倾斜角度和倾斜方向,即假定一个正交的三分量地震记录的垂直分量偏离垂向时,沿水平方向极化的地震波能量将被转换到垂直分量上去,反之亦然。这样会造成地震记录的不同分量具有相关性。通过计算旋转后的水平分量与垂直分量间的转换函数,从而可以估算出OBS台站垂直分量倾斜的角度和方向。而水平分量的方位角则参考刘晨光等(2014)和Hung等(2021),他们利用瑞雷波极化方法来确定OBS水平分量的方位角,即通过瑞雷波在垂直分量和径向分量上极化且二者之间有90°的相位差这一特性,将水平分量旋转不同的角度,最匹配瑞雷波极化特性的角度则为径向,然后与用台站和地震的经纬度确定的径向相比较得出该台站水平分量的方位角。最后通过对多个地震获得的同一台站的水平分量方位角作统计分析来确定该台站的最终水平分量方位角。

1.1.1 远震数据和区域性地震数据:

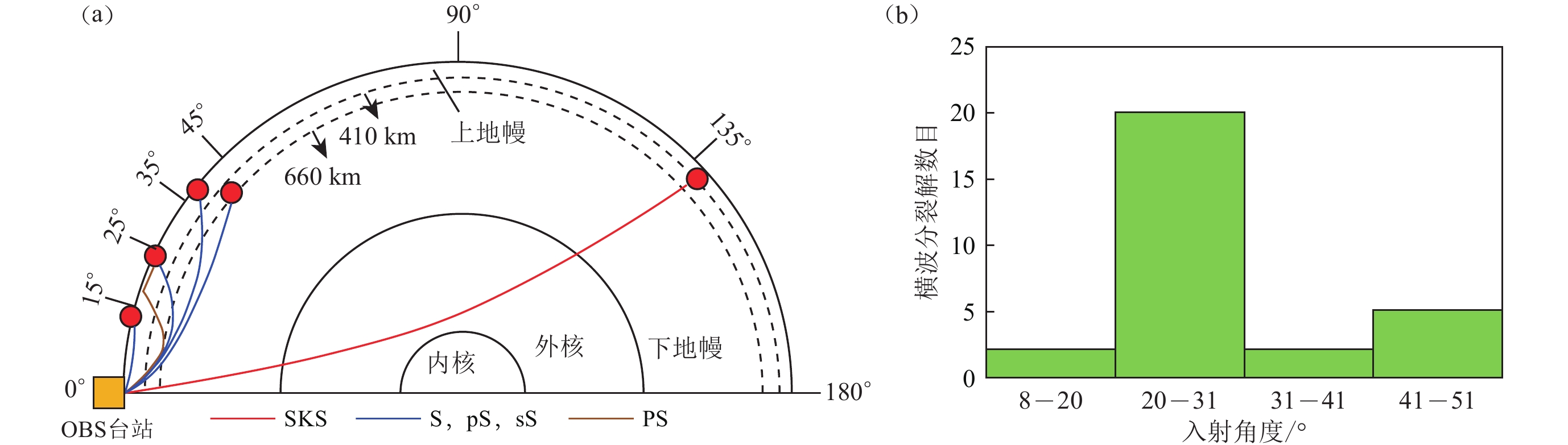

为了获得南海海盆上地幔的各向异性特征,利用震中距大于85°的远震产生的XKS (PKS/SKS/SKKS)震相进行横波分裂分析。由于XKS震相传播经过液体外核后只保留了SV分量,因此从核幔边界到台站的射线经过的介质除非存在各向同性,否则在台站只能观测到SV波,不会在切向分量上观测到明显的SH波。另外,由于XKS波近于垂直入射(图3),直接反映台站下方的各向异性,具有很高的横向分辨率。最后XKS能量较强,与其它震相如S震相分离,容易识别。

![]() 图 3 (a) 利用Taup软件并采用IASP91速度模型得到的SKS,S,pS,sS和PS震相射线路径示意图;(b)文中提供有用横波分裂解的S震相的入射角度统计图Figure 3. (a) Schematic raypaths of SKS,S,pS,sS,and PS phases obtained using the Taup package and the IASP91 velocity model (Kennett,Engdahl,1991;Crotwell et al,1999);(b) Statistical histogram of the incident angles of the S phases used in shear-wave splitting

图 3 (a) 利用Taup软件并采用IASP91速度模型得到的SKS,S,pS,sS和PS震相射线路径示意图;(b)文中提供有用横波分裂解的S震相的入射角度统计图Figure 3. (a) Schematic raypaths of SKS,S,pS,sS,and PS phases obtained using the Taup package and the IASP91 velocity model (Kennett,Engdahl,1991;Crotwell et al,1999);(b) Statistical histogram of the incident angles of the S phases used in shear-wave splitting同样地,为了分析南海周边及海盆下的平均地幔各向异性,本文还利用了震中距10°—45°的地震激发的横波如S,SS及ScS震相(图3)。这些震相虽然横向分辨率较差,但具有较好的深度分辨率,其主要采样区域为上地幔,因此可以较准确地获取其传播路径上的上地幔各向异性平均特征,恰好与XKS等经过地核的震相互补。此外,OBS地震数据的获取非常不易,所有的数据都弥足珍贵,值得深度挖掘。

基于已经获取的OBS地震数据,从美国地质调查局(United States Geological Survey,缩写为USGS)的国家地震信息中心(National Earthquake Information Service,缩写为NEIC)分别下载了震中距大于85°以及MW>6.0的地震目录用于XKS分裂分析和震中距在10—45°之间以及5.0<MW<8.0的地震目录用于S震相分裂分析,并根据这些地震目录整理对应地震事件的波形数据。经过横波分裂分析最终得到提供高质量SKS分裂解的远震2次、S震相分裂解的地震20次,地震目录信息如表2所示,地理位置分布如图2所示。需要注意的是,并非每个OBS台站都能记录到表2中所有地震的高信噪比地震信号,所以本研究中得到的有效横波分裂结果远小于表2中地震数与台站数的乘积。

表 2 挑选后可用于横波分裂的地震事件信息Table 2. The information of selected events used for shear wave splitting事件序号 年-月-日 儒略日 发震时刻 纬度 经度 震源深度/km MW 注释 1 2012-08-27 240 043719.43 12.139°N 88.590°W 28.0 7.3 远震 2 2012-11-07 312 163546.69 13.963°N 91.854°W 24.0 7.4 远震 3 2012-04-29 120 015751.90 3.059°S 136.109°E 18.4 5.2 区域震 4 2012-05-23 144 150225.31 41.335°N 142.082°E 46.0 5.9 区域震 5 2012-06-01 153 065620.24 0.720°S 133.269°E 25.0 5.8 区域震 6 2012-06-29 181 210733.86 43.433°N 84.700°E 18.0 6.3 区域震 7 2012-07-16 198 163310.08 1.296°S 137.053°E 13.1 5.6 区域震 8 2012-07-25 207 002745.26 2.707°N 96.045°E 22.0 6.4 区域震 9 2012-08-12 225 104706.45 35.661°N 82.518°E 13.0 6.2 区域震 10 2012-08-14 227 025938.46 49.800°N 145.064°E 583.2 7.7 区域震 11 2012-09-03 247 182305.23 10.708°S 113.931°E 14.0 6.1 区域震 12 2012-09-07 251 031942.53 27.575°N 103.983°E 10.0 5.5 区域震 13 2012-10-08 282 114331.42 4.472°S 129.129°E 10.0 6.1 区域震 14 2012-10-17 291 044230.40 4.232°N 124.520°E 32.6 6.0 区域震 15 2012-11-27 332 025906.52 2.952°S 129.219°E 11.2 5.7 区域震 16 2014-07-11 192 192200.82 37.005°N 142.452°E 20.0 6.5 区域震 17 2014-07-20 201 183247.79 44.642°N 148.784°E 61.0 6.2 区域震 18 2014-08-03 215 083013.57 27.189°N 103.409°E 12.0 6.2 区域震 19 2014-08-06 218 114522.68 7.274°S 128.036°E 10.0 6.2 区域震 20 2014-09-10 253 051653.21 18.400°N 125.125°E 30.0 5.9 区域震 21 2014-09-17 260 061445.41 13.764°N 144.429°E 130.0 6.7 区域震 22 2014-11-18 322 044716.63 1.869°N 126.475°E 30.0 5.8 区域震 1.1.2 地震数据预处理

由于OBS地震数据可能存在垂直分量倾斜和钟漂,以及水平分量的方位角未知,因而在处理OBS数据时需要采取相对陆上地震数据额外的处理步骤。在进行横波分裂分析之前,对收集的南海海盆OBS天然地震事件的波形数据按以下步骤进行预处理:① 去除每一地震三分量波形数据的线性趋势和均值;② 对存在钟漂的台站记录的地震数据进行钟漂校正;③ 对垂直分量倾斜角度大于5°的台站记录的三分量地震数据进行倾斜校正;④ 对所有OBS台站水平分量进行方位角校正;⑤ 选取目标震相信噪比高的地震事件;⑥ 对地震事件的目标震相进行时频分析,确定滤波频段。

在进行钟漂校正、倾斜和方位角校正时,采用表2中的相关数据(刘晨光等,2014;Le et al,2018;Hung et al,2021)。还利用XKS震相极性分析方法确定了OBS的水平分量的方位角,并与表2中的水平分量方位角进行了对比,结果显示两者反演得到的角度相差在5°—10°的范围(Li et al,2016)。以上结果验证了利用XKS震相确定OBS水平分量方位角的可行性,同时也为检验仪器稳定性和数据质量提供了一种重要方法。

此外,在做横波分裂分析时,对高信噪比的S波信号进行频谱分析,以获取相对准确的滤波频段。一般来说,高信噪比S波能量应该在径向/切向上均匀分布,或者在径向上能量较高。但在实际数据处理的过程中,我们发现相当多的S波能量集中在切向分量上,而在径向分量上几乎没有能量分布。选取了一个实例进行分析,从Harvard大学Global CMT (Centroid Moment Tensor)中心下载对应的震源机制解(Dziewonski et al,1981),根据对应地震的断层参数和弹性波的震源辐射模式计算该地震的P/SV/SH波的辐射波场,发现台站方位接收到的SH波的能量振幅远大于SV波的振幅,从而推测S波在切向分量上的高能量是由该地震的震源机制引起的(李琳,2016)。

1.2 横波分裂方法

当横波经过各向异性介质时,会分裂为波速不同、极性正交的快波和慢波。通过提取快波极化方向ϕ和快慢波分裂时间δt,可研究传播介质的各向异性。其中快波极化方向ϕ指示地壳和地幔的应力/应变方向,而快慢波分裂时间δt则代表介质各向异性强度。

传统的横波分裂方法主要有四种:切向能量最小化方法、最小特征值最小化方法、互相关方法以及多道分析方法(Bowman,Ando,1987;Silver,Chan,1988,1991;Kuo et al,1994;Chevrot,2000)。互相关方法认为由于快慢波是由同一横波分裂而成,在对快慢横波进行分离和时间延迟校正后快慢横波的波形应该具有高度的相似性,因而采用互相关函数作为波形相关性的判断依据。

这四种方法相比较,切向能量最小化方法稳定性比较好,但主要适用于穿过地球液体外核的地核震相XKS,如SKS,PKS,SKKS;最小特征值最小化方法除了适用XKS震相外,还可用于S和s等其它震相,但解的稳定性不如切向能量最小化方法;互相关方法适用于多种震相,但即使是两个噪声信号也可以做互相关,因此要求对地震震相的信噪比有较好把控;多道分析方法也适用于多种震相,但只有在地震方位角分布较好的情况下才能得出比较可信的结果(薛梅,2008)。本文由于地震方位角分布有限,仅采用了前三种方法来进行横波分裂分析。

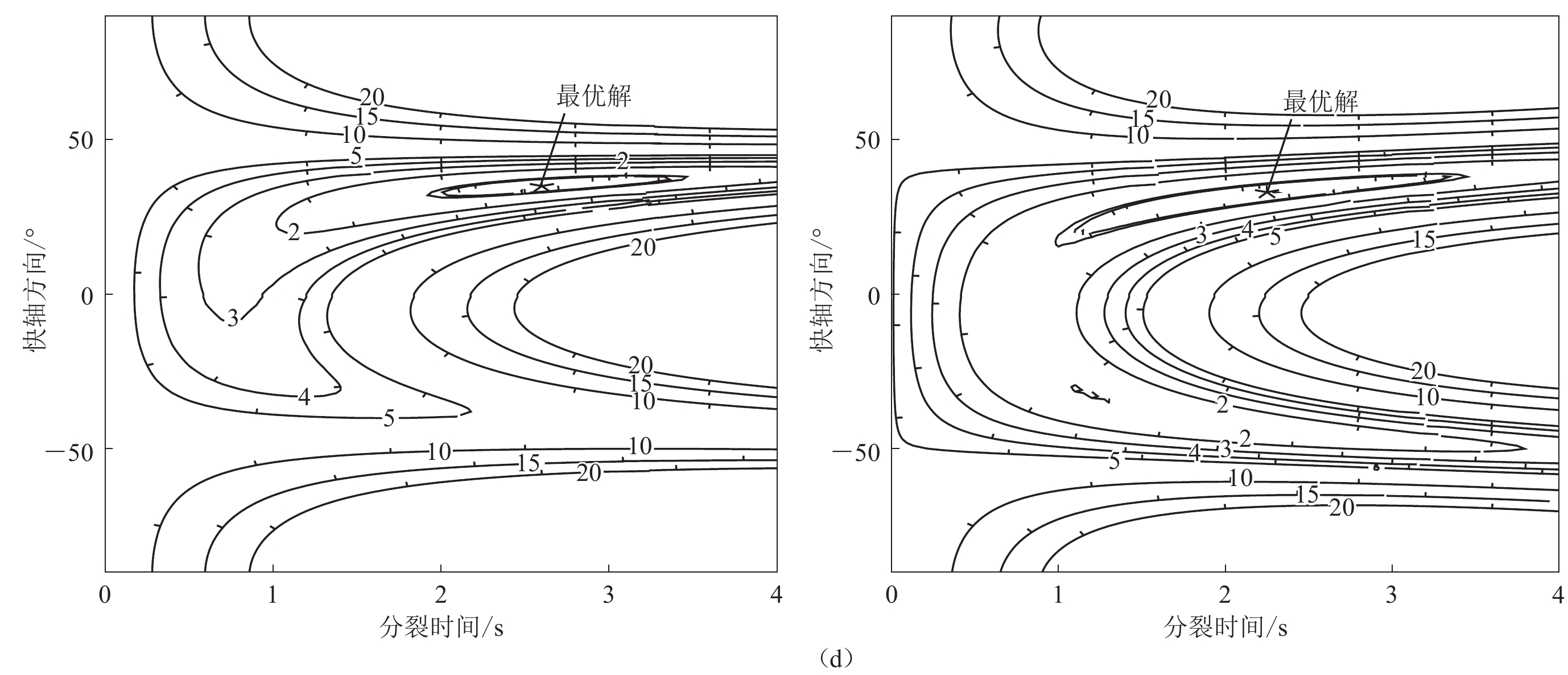

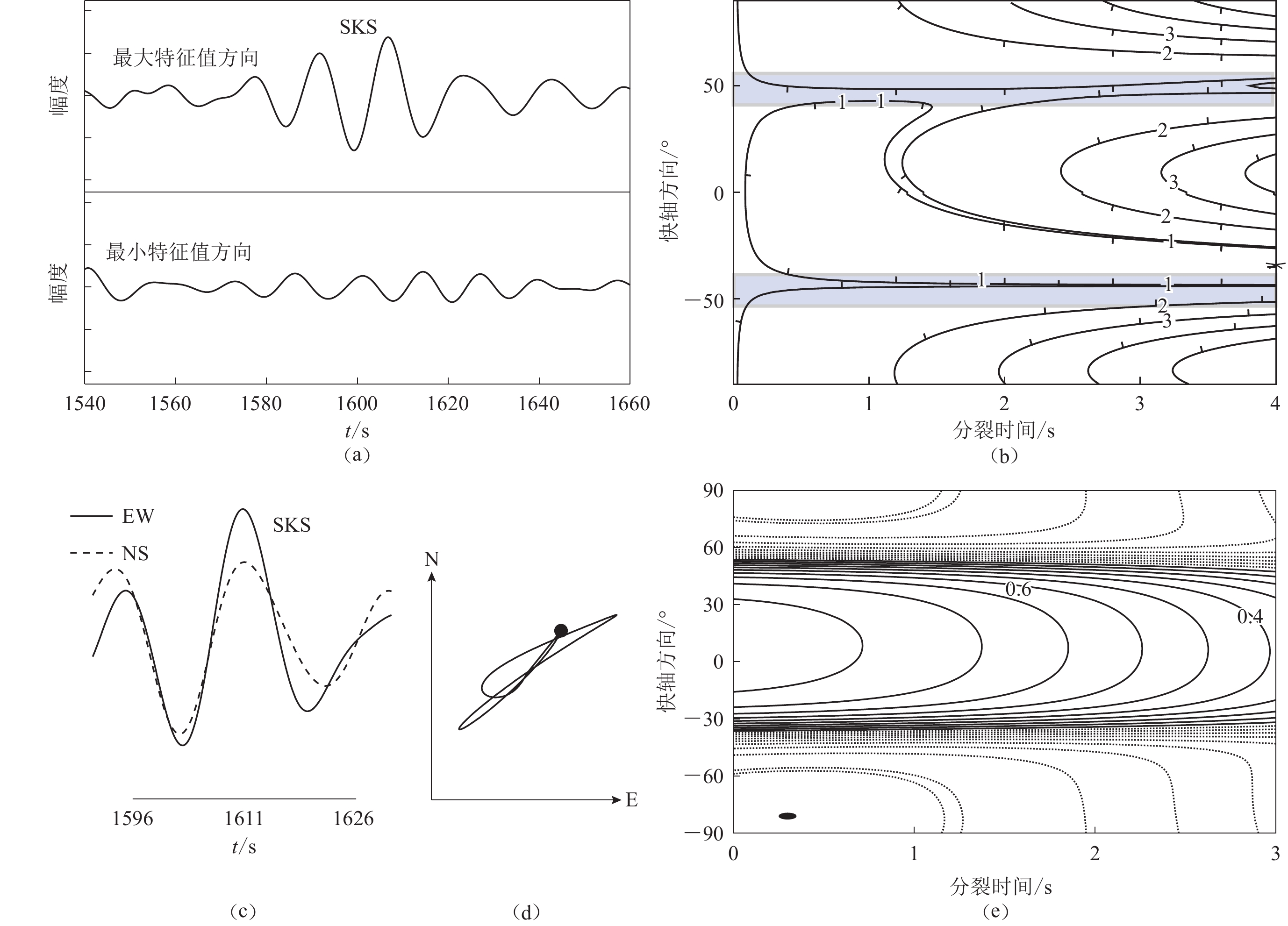

为了展示地震数据的质量以及不同横波分裂方法的结果比较,图4—6展示了一些地震数据及横波分裂结果。图4针对台站HY6记录的2012年11月7日危地马拉地震激发的PKS震相,比较了切向能量最小化和最小特征值最小化两种方法得到的横波分裂结果。可以看到PKS震相的信噪比较高,两种方法经过延迟时间校正后快慢波的波形一致性均较好,PKS震相的质点振动模式由校正前的椭圆形变为校正后的线性,且两种方法获得的横波分裂的快轴方向和分裂时间一致性较好。

![]() 图 4 采用切向能量最小化(左)和最小特征值最小化(右)方法对HY16台站记录的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的PKS震相进行横波分裂分析(a)—(c)横波分裂校正前后PKS震相滤波后的地震波形、投影到快/慢轴的波形及质点振动图(由原始的椭圆状线性化)Figure 4. Shear wave splitting analysis on the PKS phase excited by the Guatemalan coastal earthquake on November 7,2012 recorded at station HY16 using the tangential energy minimization (left) and the minimum eigenvalue minimization (right) methods(a)−(c) The filtered seismic waveforms,waveforms projected onto the fast /slow axis and the particle motions which arelinearized from the original elliptical shape of the PKS phase before and after correcting anisotropy

图 4 采用切向能量最小化(左)和最小特征值最小化(右)方法对HY16台站记录的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的PKS震相进行横波分裂分析(a)—(c)横波分裂校正前后PKS震相滤波后的地震波形、投影到快/慢轴的波形及质点振动图(由原始的椭圆状线性化)Figure 4. Shear wave splitting analysis on the PKS phase excited by the Guatemalan coastal earthquake on November 7,2012 recorded at station HY16 using the tangential energy minimization (left) and the minimum eigenvalue minimization (right) methods(a)−(c) The filtered seismic waveforms,waveforms projected onto the fast /slow axis and the particle motions which arelinearized from the original elliptical shape of the PKS phase before and after correcting anisotropy![]() 图 4 采用切向能量最小化(左)和最小特征值最小化(右)方法对HY16台站记录的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的PKS震相进行横波分裂分析(d)能量等值线图,能量被校正到最小的那个点即为最优解(星号)Figure 4. Shear wave splitting analysis on the PKS phase excited by the Guatemalan coastal earthquake on November 7,2012 recorded at station HY16 using the tangential energy minimization (left) and the minimum eigenvalue minimization (right) methods(d) Contours of energy and the point where the energy corrected to the minimum is the optimal solution (asterisk)

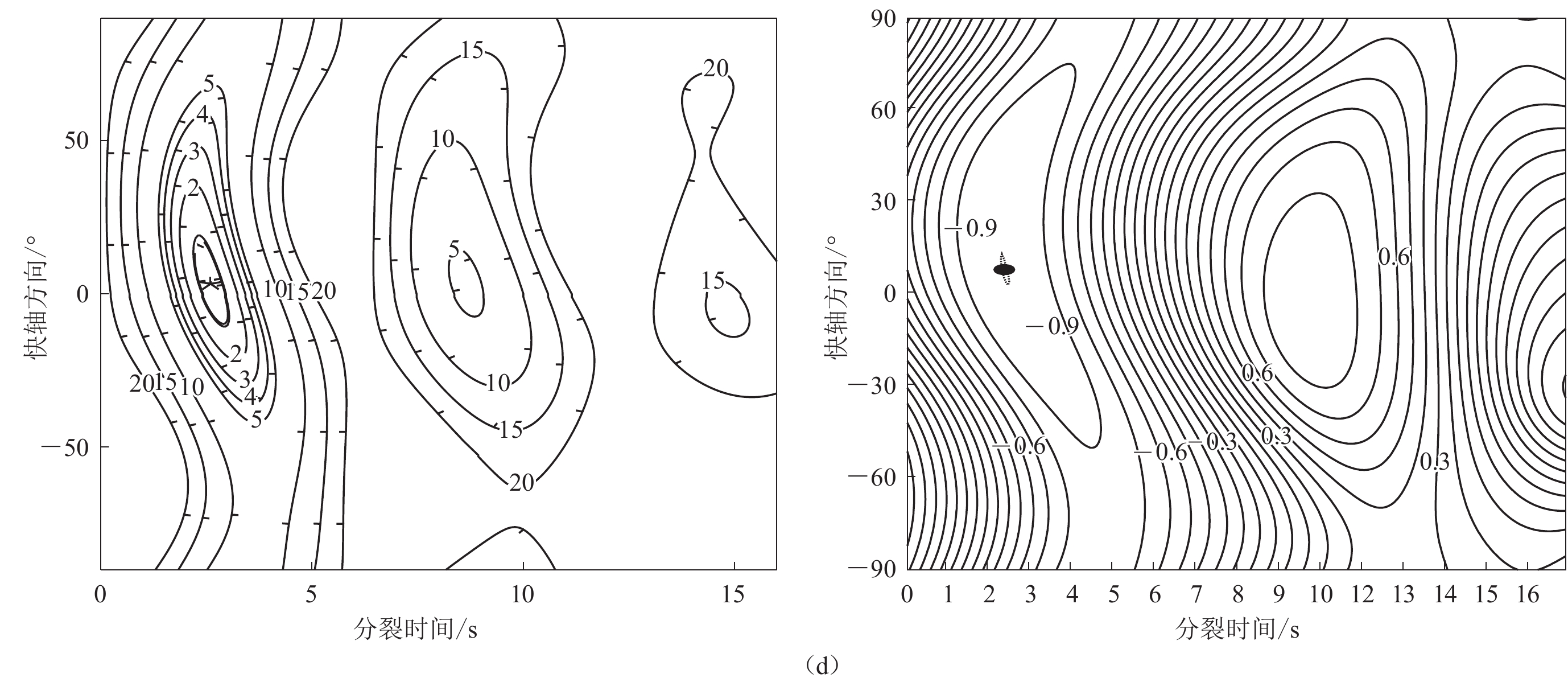

图 4 采用切向能量最小化(左)和最小特征值最小化(右)方法对HY16台站记录的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的PKS震相进行横波分裂分析(d)能量等值线图,能量被校正到最小的那个点即为最优解(星号)Figure 4. Shear wave splitting analysis on the PKS phase excited by the Guatemalan coastal earthquake on November 7,2012 recorded at station HY16 using the tangential energy minimization (left) and the minimum eigenvalue minimization (right) methods(d) Contours of energy and the point where the energy corrected to the minimum is the optimal solution (asterisk)![]() 图 6 采用最小特征值最小化(左)和波形旋转互相关(右)方法分析HY08台站记录的2012年8月14日日本本州东部区域M7.7地震激发的区域S震相的横波分裂结果(a)—(c)为横波分裂校正前后PKS震相的地震波形、投影到快慢轴的波形及质点振动图(原始的椭圆状线性化),其中右侧图采用的是质点的位移而非质点的振动速度,下同Figure 6. The S-phases are triggered by the M7.7 earthquake in the eastern region of Honshu,Japan on August 14,2012 recorded at station HY08,and a comparison is also made between the shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (left) and the cross-correlation (right)(a)−(c) The filtered seismic waveforms,waveforms projected onto the fast /slow axis and the particle motions which are linearized from the original elliptical shape of the PKS phase before and after correcting anisotropy,figures in the right column use displacements rather than vibration velocities of the ground,the same below

图 6 采用最小特征值最小化(左)和波形旋转互相关(右)方法分析HY08台站记录的2012年8月14日日本本州东部区域M7.7地震激发的区域S震相的横波分裂结果(a)—(c)为横波分裂校正前后PKS震相的地震波形、投影到快慢轴的波形及质点振动图(原始的椭圆状线性化),其中右侧图采用的是质点的位移而非质点的振动速度,下同Figure 6. The S-phases are triggered by the M7.7 earthquake in the eastern region of Honshu,Japan on August 14,2012 recorded at station HY08,and a comparison is also made between the shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (left) and the cross-correlation (right)(a)−(c) The filtered seismic waveforms,waveforms projected onto the fast /slow axis and the particle motions which are linearized from the original elliptical shape of the PKS phase before and after correcting anisotropy,figures in the right column use displacements rather than vibration velocities of the ground,the same below![]() 图 6 采用最小特征值最小化(左)和波形旋转互相关(右)方法分析HY08台站记录的2012年8月14日日本本州东部区域M7.7地震激发的区域S震相的横波分裂结果(d) 等值线图,能量和相关系数分别被校正到最小和最大的那个点即为最优解Figure 6. The S-phases are triggered by the M7.7 earthquake in the eastern region of Honshu,Japan on August 14,2012 recorded at station HY08,and a comparison is also made between the shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (left) and the cross-correlation (right)(d) Contour maps. The point where the energy and correlation coefficient are corrected to the minimum and maximum,respectively,is the optimal solution (asterisk)

图 6 采用最小特征值最小化(左)和波形旋转互相关(右)方法分析HY08台站记录的2012年8月14日日本本州东部区域M7.7地震激发的区域S震相的横波分裂结果(d) 等值线图,能量和相关系数分别被校正到最小和最大的那个点即为最优解Figure 6. The S-phases are triggered by the M7.7 earthquake in the eastern region of Honshu,Japan on August 14,2012 recorded at station HY08,and a comparison is also made between the shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (left) and the cross-correlation (right)(d) Contour maps. The point where the energy and correlation coefficient are corrected to the minimum and maximum,respectively,is the optimal solution (asterisk)信噪比较高的横波震相并不总会得到横波分裂解,有时候会得到空解(Null results)。空解的出现对XKS震相经过的介质有三种可能的解释:① 是视各项同性的;② 是各向异性的,且快轴方向与切向方向一致;③ 是各向异性的,且快轴方向与径向一致(Xue,Allen,2005)。针对图4所展示的同一地震,图5展示了对台站HY17记录到的SKS震相进行横波分裂分析得到空解的举例,并展示了最小特征值最小化和互相关两种横波分裂方法得到的空解特征:最小特征值方向的SKS震相的能量为零或者与背景噪声相当;互相关方法中原始的水平方向的质点位移运动图呈线性;在快轴方向和分裂时间域进行2D搜索,使用两种方法分别计算最小特征值方向的SKS波能量和快慢波相关系数等值线图,针对空解,两种方法获得的等值线图均沿两个候选的快轴方向呈条带状分布。

![]() 图 5 采用最小特征值最小化(a-b)和互相关横波分裂(c-e)方法分析HY17台站记录到的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的SKS震相得到的空解特征(a)表示SKS震相投影到最大及最小特征值方向的波形图;(b)为最小特征值方向能量的等值线图;(c)代表N-S和E-W向地震波位移记录;(d)表示质点运动图;(e)表示互相关方法得到的快慢波相关系数等值线图,两种方法的空解特征均为等值线图沿两个候选的快轴方向呈条带状分布Figure 5. Examples of null results obtained through shear wave splitting analysis of the SKS phase excited by the November 7,2012 Guatemalan coastal earthquake recorded at HY17 station,and a comparison of the null results,obtained using two shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (a-b) and the cross-correlation methods (c-e)(a) The SKS phases projected onto the directions of the maximum and minimum eigenvector;(b) The contours of the energy in the direction of the minimum eigenvector;(c) Seismic wave displacements in the N-S and E-W directions;(d) The particle motion diagram;(e) The contours of the cross-correlation coefficients between candidate fast and slow waves. Note that the common features of both methods for null results are that the contours are distributed in strips along the two candidate fast directions

图 5 采用最小特征值最小化(a-b)和互相关横波分裂(c-e)方法分析HY17台站记录到的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的SKS震相得到的空解特征(a)表示SKS震相投影到最大及最小特征值方向的波形图;(b)为最小特征值方向能量的等值线图;(c)代表N-S和E-W向地震波位移记录;(d)表示质点运动图;(e)表示互相关方法得到的快慢波相关系数等值线图,两种方法的空解特征均为等值线图沿两个候选的快轴方向呈条带状分布Figure 5. Examples of null results obtained through shear wave splitting analysis of the SKS phase excited by the November 7,2012 Guatemalan coastal earthquake recorded at HY17 station,and a comparison of the null results,obtained using two shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (a-b) and the cross-correlation methods (c-e)(a) The SKS phases projected onto the directions of the maximum and minimum eigenvector;(b) The contours of the energy in the direction of the minimum eigenvector;(c) Seismic wave displacements in the N-S and E-W directions;(d) The particle motion diagram;(e) The contours of the cross-correlation coefficients between candidate fast and slow waves. Note that the common features of both methods for null results are that the contours are distributed in strips along the two candidate fast directions针对震中矩0—45°地震激发的S震相,图6展示了一个横波分裂的例子,针对HY08记录的2012年8月14日日本本州东部区域M7.7地震激发的区域S震相,采用最小特征值最小化方法和互相关方法对S震相进行横波分裂,并对比得到的结果。可以看到S震相的信噪比较高,两种方法经过延迟时间校正后快慢波的波形一致性均较好,PKS震相的质点振动模式由校正前的椭圆形变为校正后的线性,且两种方法获得的横波分裂的快轴方向和分裂时间一致性较好。

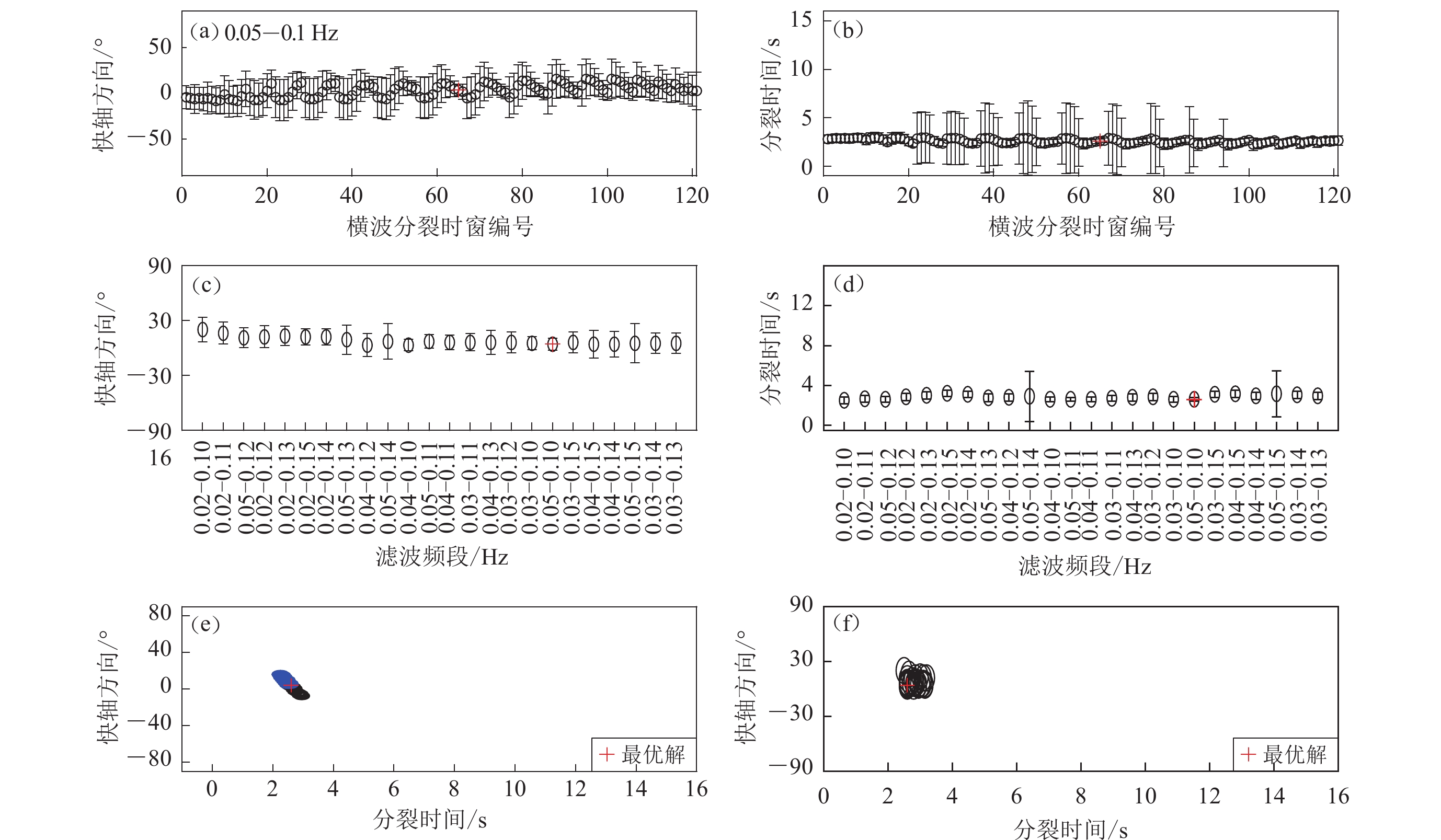

在进行横波分裂分析时,为了避免人工选取滤波频段和横波时窗对分裂结果的影响,应用了针对数据窗口长度和滤波频段的聚类分析(图7)来评估不同时窗和滤波频段对分裂结果的影响,以寻找统计学上客观稳定的分裂解(Teanby et al,2004;Xue et al,2013)。其中,滤波频段是通过傅里叶变换获得目标震相的频谱图,分析目标震相能量主要集中的频段。经过频谱分析发现,全球性地震数据的XKS震相的频段大都在0.02—0.1 Hz,而区域性地震的S震相的频段主要为0.02—0.2 Hz,造成两者差异的原因是震中距的不同,震中距相对小的地震产生高频地震信号到达台站时能量衰减较小。在针对不同频段的结果进行聚类分析时,低转角频率的变化范围一般为0.02—0.06 Hz,高转角频率的范围一般为0.1—0.15 Hz。关于横波分裂窗口的选择,需要注意的是:① 横波分裂时间窗口应包含目标横波震相的到达时间;② 横波分裂时窗的长度应该大于一个且小于两个横波震相周期,窗口太长意味着可能会包含其它的震相,造成对分裂结果的错误解释,而窗口长度小于一个周期代表只有小段横波波形匹配,这样的横波分裂结果失去真实性;③ 由噪音或者滤波引起的周期跳跃(cycle skipping),可能会产生多个分裂解,而一个好的横波分裂结果应该只有一个稳定的分裂解。为了避免周期跳跃,时窗起始点应稍许早于横波震相的到达时间,并对比不同频段滤波后的横波分裂结果,从而增加结果的稳定性。

![]() 图 7 HY08地震−台站对采用最小特征值最小化方法的横波分裂结果进行聚类分析实例(a-b)为图6所示的在0.05—0.1 Hz滤波频段针对不同横波分裂时窗得到的快轴方向和分裂时间;(c-d)为针对不同滤波频段获得的最优快轴方向和分裂时间;(e-f)为0.05-0.1 Hz和不同滤波频段的聚类分析结果,其中相同颜色的解表示通过聚类分析后划分为同一类的解Figure 7. An example of clustering analysis on shear wave splitting results obtained using the minimum eigenvalue minimization method for the earthquake-station HY08 pair(a-b) The fast directions and splitting times obtained at different splitting windows for the frequency band of 0.05−0.1 Hz in fig. 6;(c-d) The optimum fast directions and splitting times obtained at different filtering frequency bands;(e-f) The corresponding clustering analysis results for the frequency band of 0.05−0.1 Hz and for different frequency bands,where solutions with the same color represent solutions that are classified into the same class after clustering analysis

图 7 HY08地震−台站对采用最小特征值最小化方法的横波分裂结果进行聚类分析实例(a-b)为图6所示的在0.05—0.1 Hz滤波频段针对不同横波分裂时窗得到的快轴方向和分裂时间;(c-d)为针对不同滤波频段获得的最优快轴方向和分裂时间;(e-f)为0.05-0.1 Hz和不同滤波频段的聚类分析结果,其中相同颜色的解表示通过聚类分析后划分为同一类的解Figure 7. An example of clustering analysis on shear wave splitting results obtained using the minimum eigenvalue minimization method for the earthquake-station HY08 pair(a-b) The fast directions and splitting times obtained at different splitting windows for the frequency band of 0.05−0.1 Hz in fig. 6;(c-d) The optimum fast directions and splitting times obtained at different filtering frequency bands;(e-f) The corresponding clustering analysis results for the frequency band of 0.05−0.1 Hz and for different frequency bands,where solutions with the same color represent solutions that are classified into the same class after clustering analysis要通过聚类分析确定某一横波震相在某一台站的最优横波分裂解,首先固定某一频段,对该频段围绕横波震相选取不同长度的时窗进行分析获得多个横波分裂解,然后对多个横波分裂解进行聚类分析得到该频带的最优横波分裂解;对不同频段重复上述步骤获得各个频段的最优横波分裂解,然后针对这些不同频带的横波分裂解进行聚类分析,获得该台站该横波震相的最终最优解。这里选取的时间步长为0.5 s,频率步长为0.01 Hz。以图6所示的地震激发的S震相为例,以最小特征值最小化方法获得横波分裂解为例,图7显示了对台站HY08的S震相分裂解分别对时窗和频率进行聚类分析来获得最终的最优解的例子。这个例子中展示了横波分裂解随时窗和频段略有变化,但总体是稳定的。

2. 横波分裂结果

为了确保结果的可靠性,我们采取以下原则对横波分裂结果进行筛选:① 人工选择高信噪比XKS,S或ScS震相;② 经过各向异性校正后,横波的质点运动图由椭圆线性化;③ 旋转得到的快慢波波形具有很高的相似性;④ 校正后,XKS震相的切向能量接近背景噪声水平,最小特征值方法求得的最小特征值对应方向的能量接近背景噪声水平,相关分析得到快慢波的相关系数较大;⑤ 最后代表误差的等值线分布图能很好地圈定一个稳定解,且快轴的误差不超过±22.5°,XKS震相的分裂时间不应大于4 s,由于区域地震的横波路径较长,途经的地质结构较复杂,各向异性来源较多,所以分裂时间相对较大但不应大于12 s,且分裂时间的误差均不超过±1.0 s;⑥ 对于同一个地震数据,利用三种横波分裂方法得到的横波分裂解具有较好的一致性。

总而言之,一个好的横波分裂结果,不仅要求能够把目标震相的切向能量或者最小特征值方向的能量最小化到地震背景噪声水平,而且分裂结果的误差也要尽可能的小,不同方法得到的结果一致性较高。同时,还要保证分裂结果在一定范围的时间窗口和滤波频段内都是稳定的,说明其可靠性。

2.1 XKS震相横波分裂结果与解释

产生XKS震相的震中距一般在85°左右,在南海海盆接收到的XKS震相信号,其震源的地理位置大部分位于环太平洋俯冲带的东南太平洋区段,以中美洲海沟为代表。为了保证较高的信噪比,筛选后远震的震级(MW)大于5.9。总体来说,可用于XKS横波分裂的远震数目较少。本文中一共有5个OBS台站接收到来自于两个全球性地震的高信噪比的XKS信号,同时采用切向能量最小化方法、最小特征值最小化方法和互相关方法对XKS波进行横波分裂分析,最终反演结果列于表3。

表 3 远震的横波分裂结果Table 3. The shear-wave splitting results for teleseismic earthquakes台站 事件 后方位角/° 震中距/° 震相 ϕ/° δt/s 方法 HY02 1 46.2 142.6 SKKS 46.2;−43.8 空解 切向能量 46.2;−43.8 空解 最小特征值 46.2;−43.8 空解 互相关 HY10 2 46.5 139.7 PKS 46.5;−43.5 空解 切向能量 46.5;−43.5 空解 最小特征值 46.5;−43.5 空解 互相关 HY15 2 45.5 138.1 SKKS 45.5;−44.5 空解 切向能量 45.5;−44.5 空解 最小特征值 45.5;−44.5 空解 互相关 PKS 45.5;−44.5 空解 切向能量 45.5;−44.5 空解 最小特征值 45.5;−44.5 空解 互相关 HY16 2 46.2 137.6 PKS 35±1.5 2.6±0.35 切向能量 33±6.5 2.25±0.55 最小特征值 46.2;−43.8 空解 互相关 SKKS 46.2;−43.8 空解 切向能量 46.2;−43.8 空解 最小特征值 46.2;−43.8 空解 互相关 HY17 2 47.1 137.3 SKS 47.1;−42.9 空解 切向能量 空解 最小特征值 空解 互相关 空解 切向能量 PKS 47.1;−42.9 空解 最小特征值 空解 互相关 依据XKS波的分裂结果,南海海盆正下方的快波偏振方向近NE-SW向,平行于中央海盆残留洋中脊的延伸方向,延迟时间在2.5 s左右,误差在0.4—0.8 s之间。同时,分裂结果中也出现了一些空解(Null results),其候选的快波方向为近NE-SW或NW-SE方向,结合分裂解为NE-SW的快轴方向,认为这些空解指示的快轴方向应该为与分裂解一致的NE-SW方向(图8)。

XKS波在核幔边界进行了P-S波转换并近垂直入射到达接收台站,XKS波分裂结果反映的是台站一侧的核幔边界到台站正下方的各向异性特征的综合效应(图8)。一般来说,XKS波在下地幔的分裂时间小于0.2 s,转换带的分裂时间在0—0.7 s,上地幔对分裂时间的贡献在0—3.0 s,而地壳则小于0.3 s (Savage,1999;Silver,1996)。根据我们的远震横波分裂结果,延迟时间为2.25—3.25 s,主要反映的是上地幔的各向异性特征,来自上地幔物质变形引起的橄榄石的定向排列。

上地幔中橄榄石矿物的形成主要取决于地幔场的环境温度、应力、含水量及压力条件,包括A型、B型、C型、D型以及E型等组构,不同类型橄榄石矿物的长轴方向对应不同构造应力场或地幔变形的方向(Long,Becker,2010)。通过对比全球地幔流模型与横波分裂的快波方向,结果表明高温低压含水量较低的地幔中生成的A型橄榄石是最常见的地幔矿物类型,在简单剪切的地幔流及区域构造应力场的作用下,形成其晶格长轴平行于地幔流流动方向的橄榄石集合体,因而在宏观上表现为快波方向平行于区域最大剪应力的方向以及地幔流的运动方向;而在低温高压含水量较高的地幔中则生成大量的B型橄榄石矿物,其集合体的定向排列,在宏观上表现为其各向异性的快轴方向垂直于地幔流的运动方向或最大剪应力方向(Mainprice et al,2005)。

而在南海海底停止扩张,沿西南—南—东三面全被俯冲带围绕,地幔有可能存在低温高压含水的环境从而导致B型橄榄石矿物组构。但同时也要意识到,海南地幔柱或者环形俯冲引起的地幔上涌,有可能会增加地幔的温度,从而不利于B型橄榄石矿物组构的形成。本文中得到的南海海盆的NE-SW向快轴方向如果按A型橄榄石组构解释的话,与残留洋脊的走向以及南海地块向菲律宾海板块斜向俯冲的方向一致;按B型橄榄石组构解释的话,与海底扩张停止前扩张的方向以及印支板块的SW向挤出方向一致。

南海在海底扩张后期以及停止扩张后有大量海山发育,说明岩浆活动广泛(Sun et al, 2019)。而岩浆存在的形式不同,对各向异性的影响是不同的:当岩浆以熔体囊的形式存在时,表现为各向同性介质;而当岩浆以熔体层的形式存在时,快轴方向与最大应变方向垂直,类似于B型橄榄石组构(Holtzman et al,2003)。但由于SKS分裂结果不具备纵向分辨率,这里并不能量化岩浆活动对海盆观测到的各向异性的贡献大小。

2.2 区域S震相横波分裂结果与解释

区域地震的横波信号主要是S/pS/sS/PS震相,上述S震相的地震震源深度在10—583 km的范围内,通过走时计算软件Taup计算分析可得,S震相对地幔采样的最大穿透深度或者说折返深度为1095 km (图3)。由于地球的各向异性区域主要集中在上地幔,而区域地震的S波震相主要对上地幔横向采样,在各向异性强的上地幔里传播了较远的距离,导致S震相的横波分裂时间较XKS长很多,最大甚至超过10 s。另外,对数据的分析显示,不少台站记录到的S震相与pS,sS和PS震相到达的时间相近,不能分离出来,因而S类震相的横波分裂结果是震源到台站路径上的综合视横波分裂解,反映了该射线穿过上地幔的平均视各向异性,所揭示的地质历史也对应被大地构造运动主导的平均视地质历史。

区域地震的S震相分裂结果与地震震源的地理位置分布有密切关系,以台站为参考大体上可分为六个方位:① 西北方向分为东西两支,西部靠近红河断裂的射线,其快波方向近NNE向,与印度板块向欧亚板块碰撞的方向一致;东部经过青藏高原的射线其快波的偏振方向为NW-SE方向,与印度板块和欧亚板块碰撞后导致部分物质SE向流动方向一致;② 东北方向分为南北两支,北部沿日本海和东海之下传播的射线,其快轴方向为NE-SW方向,与岛弧方向以及海盆的走向一致;南支沿岛弧和海沟下方传播,其快轴方向为NW-SE,近垂直于琉球海沟的方向,或者说平行于菲律宾海板块的绝对运动方向;③ 正东方向,射线横跨菲律宾海,快轴方向为近N-S;④ 东南方向,主控的快轴方向近NE-SW向,与菲律宾海沟近平行,但在新几内亚北端的地震激发的沿与菲律宾海沟以及Halmahera海沟近平行的射线路径快轴方向为NNW-SSE,与菲律宾海沟近垂直;⑤ 南南东至正南方向,快轴为NW-SE方向,与南沙海槽、Sangihe海沟以及班达海沟近垂直;⑥ 西南方向,快轴方向为NE-SW方向,与苏门答腊海沟的位置垂直,或者说与印度—澳大利亚板块俯冲的方向一致。

表 4 区域性地震的横波分裂结果Table 4. The shear-wave splitting results obtained for regional earthquakes台站 事件 后方位角/° 震中距/° 震相 (φ±σφ)/° (δt±σδt)/s 方法 HY02 6 321.9 38.2 S,pS,sS −42±17.0 9.75±0.96 互相关 9 309.2 35.8 S,pS,sS,PS 28±4.5 2.8±0.4 最小特征值 11 185.2 26.8 S,pS,sS −47±13.0 0.75±0.23 最小特征值 −48±24.0 0.75±0.60 互相关 12 316.8 16.1 S,sS,Sn,SS −1±8.5 1.8±0.375 最小特征值 −36±25.0 0.75±0.42 互相关 HY08 3 131.4 24.7 S,pS,sS,PS −47±5 2.72±0.5 最小特征值 −11±21 1.2±0.50 互相关 4 33.0 34.6 S 50±7 2.8±0.575 最小特征值 11±22 1.15±0.39 互相关 5 132.0 21.1 S,pS,sS −34±7 1.0±0.23 最小特征值 −48;42 空解 互相关 6 322.6 41.0 S,pS,sS,PS −46±5.0 9.6±0.375 最小特征值 −49±8.0 9.85 ±0.45 互相关 7 126.7 24.3 S,pS,sS,PS 27±15.5 2.65±0.83 最小特征值 59±24.0 1.5±0.55 互相关 10 26.2 42.3 S 4±6.5 2.6±0.2 最小特征值 8±7 2.35±0.17 互相关 HY15 6 320.8 38.7 S,pS,sS,PS −38±4.5 9.6±0.28 最小特征值 −46±7.0 9.75 ±0.41 互相关 8 239.3 25.2 S,pS,sS,PS 69±9.5 6.6±1.35 最小特征值 58±6.0 7.4±0.56s 互相关 10 27.8 40.0 S 36±4.0 7.65±0.35 最小特征值 −42;48 空解 互相关 HY16 6 320.4 39.1 S,pS,sS −64±4.0 8.85±0.25 最小特征值 −63±3.0 9.0 ±0.14 互相关 11 189.2 27.3 S,pS,sS,PS −79±4.5 2.85±0.7 最小特征值 −69±2 4.65±0.24 互相关 13 151.6 23.4 S,pS,sS,PS 20±9.5 1.9±0.275 最小特征值 17±18 1.75±0.27 互相关 14 152.3 13.6 S,Sn 14±1.5 2.2±0.2 最小特征值 −67;23 空解 互相关 15 149.6 22.1 S,pS,sS,PS 42±5.0 3.25±0.85 最小特征值 54±3.0 4.9±0.43 互相关 HY17 6 320.2 39.8 S,pS,sS,PS −44±5.0 8.80±0.23 最小特征值 −45±5.0 8.95 ±0.22 互相关 B04 16 40.2 32.2 S,pS,sS,PS −67±9.0 3.55±0.775 最小特征值 −80±11 4.25±0.65 互相关 22 141.4 15.3 S,Sn,sS −79±20 2.05±0.61 互相关 B19 17 35.8 40.6 S,pS,sS,PS −34±5.5 3.1±0.15 最小特征值 18 318.0 17.6 S,Sn,sS,SS −7±2.0 3.65±0.3 最小特征值 19 151.4 24.5 S,pS,sS,PS −41±1.5 8.95±0.25 最小特征值 −41±2 9.1±0.18 互相关 20 148.9 16.9 S,Sn,sS,SS −36±3 8.05±1.0 最小特征值 −41;49 空解 互相关 21 88.1 27.1 S,sS 5±3.5 4.1±0.325 最小特征值 −12±9.0 4.85±0.35 互相关 B32 17 34.7 39.9 S,sS −26±2.0 3.65±0.2 最小特征值 19 154.5 23.7 S,pS,sS,PS −75±2.5 3.7±0.4 最小特征值 −75;15 空解 21 88.1 25.6 S,sS 7±5 2.95±0.2 最小特征值 2±10 2.95±0.4 3. 讨论

南海位于多个地质构造板块的交会处,处于复杂的构造环境下,其形成演化受到周围地质板块的构造影响(李家彪等,2002,2004;张亮,2012)。南海北部为扩张带,是华南地块的向南延伸部分,发育了一系列拆离断层和隆、坳构造带,为拉张型构造边界(钟广见等,2006)。南海南部的南侧为挤压带,受到古南海俯冲及碰撞过程的影响发育一系列叠瓦状构造,而南部北侧则与南海北部成共轭型大陆边缘。南海西部为剪切带,由于印度—欧亚板块的碰撞使得印支地块向SE构造挤出,并发育大规模走滑构造。南海东部的西侧为南海地块向吕宋岛弧俯冲,而东部的东侧则是菲律宾海板块向吕宋岛弧俯冲,形成复杂的沟弧盆体系。南海的东侧北端则与菲律宾海板块共同作用于欧亚板块,碰撞形成台湾造山带。

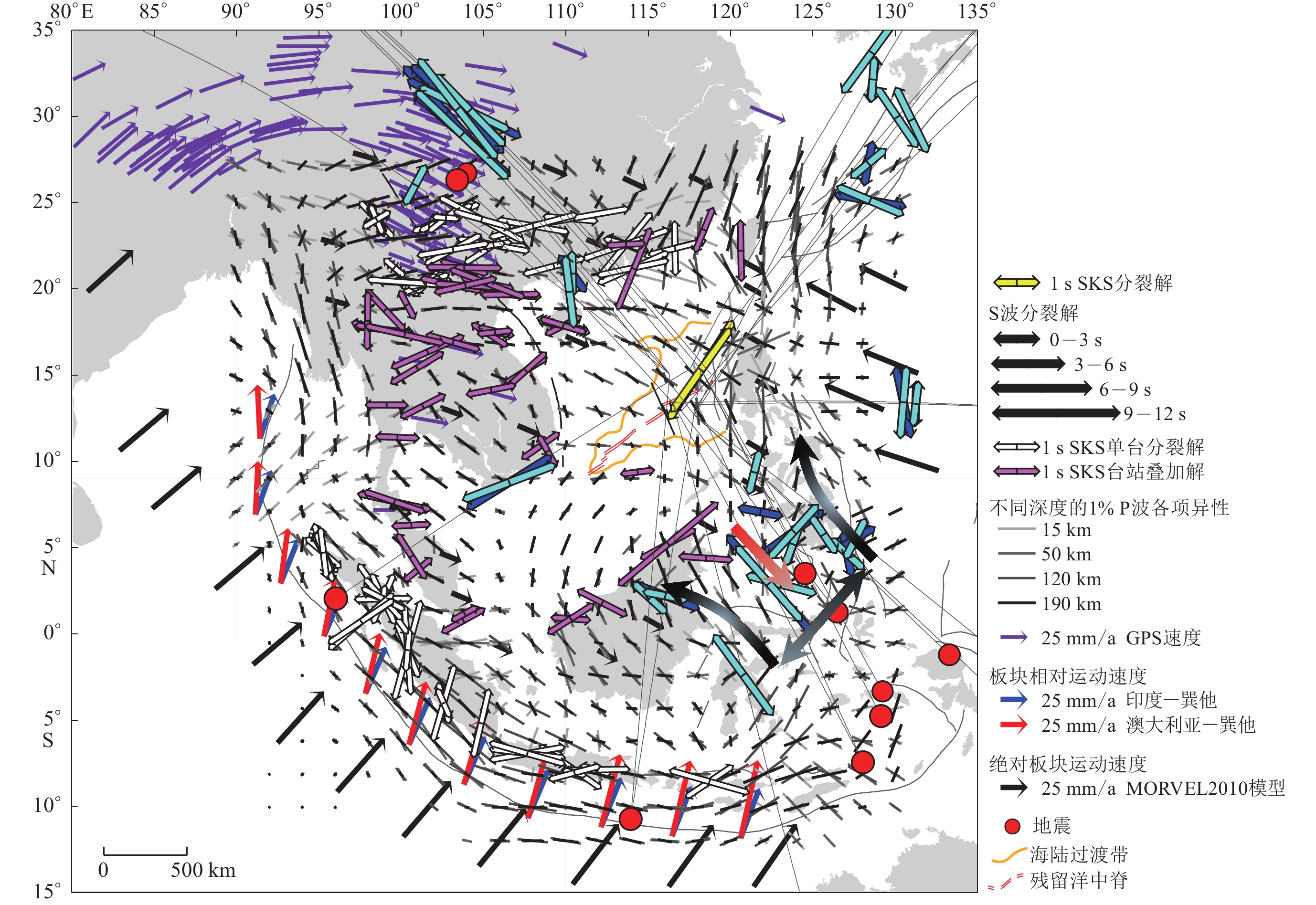

南海当前的构造运动引起的各向异性会叠加在南海构造演化历史造成的各向异性上,从而使得对获得的各向异性的解释较为复杂,尤其是从中提取造成南海形成的构造运动尤为困难。为了更好地分析南海海盆的各向异性结果,综合了本文获得的各向异性结果和前人在南海及周边地区获得XKS分裂结果、P波各向异性成像结果以及GPS和板块运动的方向,结果如图10所示。

![]() 图 10 南海海盆及周边横波分裂及P波各向异性结果比较黄色双箭头表示本研究得到的SKS分裂解;蓝色和蓝绿色双箭头分别为采用互相关方法和最小特征值最小化方法针对区域地震激发的S震相得到的横波分裂解;针对SKS震相在不同台站获得单个分裂解以及台站叠加解来自文献(Bai et al,2009; Hammond et al,2010;Huang et al,2011;Xue et al,2013;Yu et al,2018;Song et al,2021);P波各向异性结果来自Huang等(2015),其走向和长短分别代表快波的极化方向和各向异性的强度。台站东南方位马鲁古海区域根据横波分裂结果预期的该区域的地幔对流模型:黑色渐变粗实线代表Singihe板块下方与海沟平行的地幔流,板块两侧则是与板缘有关的偏转流,红色渐变粗实线则代表地幔楔里的角流,箭头指向流动方向Figure 10. Comparisons of shear wave splitting results from this study with previous ones as well as the P-wave anisotropy results in the South China Sea Basin and its surrounding areasThe yellow double arrows represent the SKS splits obtained in this study;the blue and blue-green double arrows represent the splits obtained using the cross correlation method and the minimum eigenvalue minimization method for the S-phase excited by regional earthquakes,respectively;the individual SKS splits and stacked SKS splits are from previous studies (Bai et al,2009;Hammond et al,2010;Huang et al,2011;Xue et al,2013;Yu et al,2018;Song et al,2021);the P-wave anisotropy at different depths are from Huang et al (2015),and the direction and length of the short solid lines represent fast directions and anisotropic intensities respectively. The mantle convection model of the Molucca Sea region in the southeast of the OBSs consistent with most shear wave splitting results obtained in this study: the black gradient thick solid lines represent the trench-parallel flow under the Sangihe plate and the deflection flow related to the plate edge is on both sides of the plate,and the red gradient thick solid line represents the corner flow in the mantle wedge,and the arrows indicate the flow directions

图 10 南海海盆及周边横波分裂及P波各向异性结果比较黄色双箭头表示本研究得到的SKS分裂解;蓝色和蓝绿色双箭头分别为采用互相关方法和最小特征值最小化方法针对区域地震激发的S震相得到的横波分裂解;针对SKS震相在不同台站获得单个分裂解以及台站叠加解来自文献(Bai et al,2009; Hammond et al,2010;Huang et al,2011;Xue et al,2013;Yu et al,2018;Song et al,2021);P波各向异性结果来自Huang等(2015),其走向和长短分别代表快波的极化方向和各向异性的强度。台站东南方位马鲁古海区域根据横波分裂结果预期的该区域的地幔对流模型:黑色渐变粗实线代表Singihe板块下方与海沟平行的地幔流,板块两侧则是与板缘有关的偏转流,红色渐变粗实线则代表地幔楔里的角流,箭头指向流动方向Figure 10. Comparisons of shear wave splitting results from this study with previous ones as well as the P-wave anisotropy results in the South China Sea Basin and its surrounding areasThe yellow double arrows represent the SKS splits obtained in this study;the blue and blue-green double arrows represent the splits obtained using the cross correlation method and the minimum eigenvalue minimization method for the S-phase excited by regional earthquakes,respectively;the individual SKS splits and stacked SKS splits are from previous studies (Bai et al,2009;Hammond et al,2010;Huang et al,2011;Xue et al,2013;Yu et al,2018;Song et al,2021);the P-wave anisotropy at different depths are from Huang et al (2015),and the direction and length of the short solid lines represent fast directions and anisotropic intensities respectively. The mantle convection model of the Molucca Sea region in the southeast of the OBSs consistent with most shear wave splitting results obtained in this study: the black gradient thick solid lines represent the trench-parallel flow under the Sangihe plate and the deflection flow related to the plate edge is on both sides of the plate,and the red gradient thick solid line represents the corner flow in the mantle wedge,and the arrows indicate the flow directions为了清晰起见,以下将按南海构造或地理单元分区,综合本文及前人的各向异性结果,来分析南海的各向异性特征,约束南海地质演化的模型。

3.1 南海中央海盆的各向异性结构

本文的SKS分裂结果展示了南海中央海盆的各向异性快轴方向为NE向,且分裂时间为2.5 s左右,远远大于全球平均的1 s,说明南海下方有着较强的各向异性结构(图8)。由于SKS分裂得到的各向异性代表台站下方从核幔边界到地表各向异性的积分,并通常被认为被上地幔各向异性主导,因而需要结合对南海海盆下方分层各向异性的研究来解释得到的SKS分裂结果。

遗憾的是受台站分布的影响,对南海海盆下方的各向异性研究尤其是上地幔的研究一直受限。在利用Pn波对莫霍面的各向异性研究中,仅对中南断裂以东的南海北部及中央海盆Pn波各向异性进行了研究,发现快轴方向从南到北存在变化:在南海北部海陆陆缘到大陆海洋边界快轴方向总体为NE-SW,并认为这里存在的高Pn波速度(8.0—8.1 km/s)对应大陆型岩石圈地幔;在中央海盆快轴方向变为NNW-SSE,与残余洋脊的走向近垂直,并将这里较低的Pn波速度(小于7.7 km/s)解释为消亡洋中脊残余的岩浆活动;在南部大陆海洋边界附近快轴又变回NE-SW方向(胥颐等,2007)。由于Pn波是沿着莫霍面的滑行波,它只对上地幔顶部的各向异性敏感。在中央海盆观测到的Pn波NNW-SSE的快轴方向与本研究通过SKS震相分裂获得的NE-SW方向近乎垂直。这说明Pn波的各向异性对我们的SKS观测并无显著贡献。

而对南海海盆莫霍面以下的各向异性,Huang等(2015)利用P波走时层析成像和各向异性联合反演的方法做了尝试。遗憾的是受限于台站的分布,在15—300 km深度范围,仅在南海海盆周边略有分辨率,直到更深的450—600 km的地幔过渡带深度,才真正对中央海盆具有分辨率,且横向分辨率为400 km×400 km。在50 km以内深度,各向异性较弱且快轴为近NNW-SSE,可能与弧后扩张在地幔楔引发的地幔流有关;在50 km的深度快轴变为平行于中央海盆的残留洋脊的NE-SW向;在150 至300 km的深度,海盆中央的各向异性再次变弱,且快轴又变为近W-E向,并持续到地幔过渡带顶部,而后到了地幔过渡带底部快轴方向又变为NEE-SWW。而海盆东缘靠近马尼拉海沟附近在50—300 km深度观测到了近N-S向平行于海沟的快轴方向,被解释为反映南海俯冲板块内部和/或者其周边地幔的各向异性 (Huang et al,2015)。

在南海中央海盆的有限的P波各向异性观测在50 km深度以及地幔过渡带底部获取的快轴方向与本文SKS分裂得到的快轴方向一致(图9),但综合各个深度来说,并不好直接对比这两种方法获得的结果。这里需要注意海盆300 km深度以内的P波各向异性实际上是在分辨率缺乏的基础上得到的,仅作为参考。

![]() 图 9 南海周边区域地震的S震相分裂结果蓝色短实线和蓝绿色短实线分别代表采用互相关方法和最小特征值最小化方法得到的横波分裂解Figure 9. The S-wave splitting results for regional earthquakes surrounding the South China SeaBlue solid lines and light blue solid lines represent splitting results obtained by the cross-correlation method and the smallest eigenvalue minimization method,respectively. The lengths of the lines are proportional to their splitting time,as shown in the lower left corner of the figure

图 9 南海周边区域地震的S震相分裂结果蓝色短实线和蓝绿色短实线分别代表采用互相关方法和最小特征值最小化方法得到的横波分裂解Figure 9. The S-wave splitting results for regional earthquakes surrounding the South China SeaBlue solid lines and light blue solid lines represent splitting results obtained by the cross-correlation method and the smallest eigenvalue minimization method,respectively. The lengths of the lines are proportional to their splitting time,as shown in the lower left corner of the figure因为NE-SW向的强各向异性平行于残留洋中脊走向以及南海海洋板块向吕宋岛弧俯冲的方向,我们更倾向于认为以下两种构造运动对观测到的各向异性起主导作用:一是南海海底扩张时期地幔上涌到达岩石圈在洋脊方向形成的槽然后沿洋脊方向流动,二是南海海洋板块拖拽部分地幔与其一起向NE向俯冲。

3.2 南海中央海盆到周边构造体的平均上地幔各向异性

本文利用布设于南海海盆的OBS台站接收到的南海周边发生的地震激发的S类震相来约束从这些地震到南海中央海盆路径上的平均上地幔各向异性(图10)。注意S波分裂时间较大,反映了这些地区上地幔存在强地幔各向异性。为了清晰显示,在图10中针对S波分裂时间采取了与SKS分裂时间不同的比例尺。下面主要聚焦快轴方向,根据提供有效横波分裂解的地震其分布按地震方位分区讨论:

1) 沿西北方向到青藏高原的平均上地幔各向异性。沿更西部靠近红河断裂的射线路径获取的快轴为近NE-SW,与印度板块向欧亚板块碰撞的方向一致。沿偏东经过青藏高的射线路径获取的快轴为NW-SE,与印度板块和欧亚板块碰撞后导致部分物质沿SE向挤出的方向一致,也与南海打开的方向一致。这个观测结果与这一区域的SKS横波分裂结果和P波各向异性结果一致:在红河断裂东侧,快波极化方向由北部的NEE-SWW旋转到南部的NW-SE (Bai et al,2009;Xue et al,2013;Huang et al,2015)。这与GPS观测以及该地区板块绝对运动方向一致,证实了该区域岩石圈和软流圈是耦合在一起同向运动的。

2) 沿东北方向到日本列岛的平均上地幔各向异性。偏北部沿日本海和东海的射线路径获取的快轴方向为NE-SW,与P波各向异性的方向一致,与岛弧以及海盆的走向一致,可能反映了海洋岩石圈固化的与海底扩张方向一致而与俯冲方向垂直的各向异性。偏南部沿岛弧和海沟下方的射线路径获取的快轴方向为NW-SE,近垂直于琉球海沟的方向,或者说平行于菲律宾海板块的绝对运动方向。

3) 沿正东方向横跨菲律宾海射线路径获取的平均快轴方向为近N-S。由于马来群岛的SKS分裂解仅得到空解,可以看做其下方的地幔表现为视各向同性的一个指标,对经过它的射线路径上各向异性的贡献可以忽略,这里得到的结果主要反映菲律宾海上地幔各向异性。射线大部分路径经过西菲律宾海盆,近N-S的快轴方向与西菲律宾海盆的海底古扩张方向一致,反映了固化在西菲律宾海洋岩石圈里海底扩张引起的各向异性。

4) 沿东南至正南方位,快轴的方向依次发生了改变:台站东南方位,新几内亚北端地震激发的地震波,沿与菲律宾海沟以及Halmahera海沟近平行的射线路径经过马鲁古海北缘,其快轴方向为NNW-SSE,与菲律宾海沟近垂直;再向南,邻近海沟地震的射线路径经过马鲁古海,主控快轴方向近NE-SW向,与菲律宾海沟近平行;沿南南东至正南方位至班达海沟的射线路径经过马鲁古海的南缘,获取的快轴为NW-SE,与南沙海槽、Sangihe海沟以及班达海沟近垂直。这些观测结果与和前人在这一区域的横波分裂结果一致(Di Leo et al,2012a,b;Wang,He,2020;Cao et al,2021),并在射线路径中点以北的P波各向异性快轴方向有较好的对应(Huang et al,2015)(图10)。横波分裂结果可以很好地匹配前人的地幔流模型:马鲁古海西北侧向西北俯冲的Sangihe板块,引起的马鲁古海中侧地幔楔中NW-SE向的角流,以及Sangihe板块北缘和南缘的NNW-SSE和NW-SE向偏转地幔流,Sangihe板块北缘和中部之间观测到的NE-SW向则对应Sangihe板块下的与海沟平行的板下地幔流( Cao et al,2021)。我们的分裂结果第一次给出Sangihe板块北缘存在偏转地幔流的证据。而邻近的加里曼丹岛西北侧观测到的平行于南沙海槽的SKS快轴方向NE-SW,该各向异性可能是由俯冲的古南海板块存在而引起沿海沟方向地幔偏转流造成的 (Xue et al,2013;Cao et al,2021;Song et al,2021)。俯冲的古南海板块的存在已经在层析成像中得到证实,表现为倾斜高速异常(陈立等,2012;Hall,Spakman,2015)。

5) 沿西南方向至苏门答腊的射线路径上获取的快轴方向为NE-SW方向,与印度澳大利亚板块绝对运动的方向一致,也平行于西南次海盆的走向,也与其邻近的越南南部的SKS波分裂得到的快轴方向一致,支持将越南南部SKS波分裂得的NE-SW快轴方向归于岩石圈起源的解释(Bai et al,2009)。

3.3 各向异性结果对南海演化模型的约束

南海中央海盆及周边的各向异性为各种构造运动提供了约束和支持,对南海打开的各种演化模型也提供了一些有力的约束。

各向异性结果支持两种的南海打开的演化模型:印度—欧亚板块碰撞带至南海中央海盆的NW-SE向强上地幔平均各向异性符合南海的碰撞驱动挤出模型;而在加里曼丹沿巴拉望海沟与海沟平行的快轴方向以及海沟以南与古南海俯冲方向一致的各向异性结果支持古南海俯冲板块拖拽模型。各向异性结果不能证实亦不能证伪“大西洋型”海底扩张模型、弧后扩张模型和板缘破裂模型。各向异性结果似乎不支持的模型为地幔上涌驱动模型。从南海中央海盆以及周边的各向异性结果看,没有显示南海海盆下方存在规则的地幔柱上升流以及到达岩石圈底部后向四周扩散的地幔流会引发各向异性的模式。也不能排除存在非理想的地幔柱上涌模式,而海盆各向异性观测特别有限不能识别。

4. 结论与展望

4.1 结论

SKS分裂结果展示了南海中央海盆下方存在快轴方向为NE向的强各向异性,平行于残留洋中脊的方向以及南海海洋板块向吕宋岛弧俯冲的方向,其成因可能与海底扩张时期沿洋脊方向的地幔流以及南海海洋板块俯冲拖拽的地幔流有关。

南海及其周边上地幔存在强各向异性,且不同方位观测到的各向异性不同,快轴方向与前人SKS横波分裂结果、GPS和板块运动一致,与区域的构造运动和地幔对流模型对应较好。如沿西北方向到青藏高原的平均上地幔快轴方向由西边的NE-SW转向东边的NW-SE,与印度板块和欧亚板块碰撞后导致部分物质沿SE向挤出的方向一致,也与南海打开的方向一致。又如沿东南至正南方向快轴发生了从NNW-SSE到NE-SW最后到NW-SE的变化,很好地匹配前人的地幔流模型,即向西北俯冲的Sangihe板块引起地幔楔中NW-SE向的角流,俯冲板块下存在与海沟平行的板下地幔流,以及Sangihe板块两侧存在的NNW-SSE和NW-SE向偏转地幔流。沿西南方向至苏门答腊的上地幔NE-SW各向异性与与印度澳大利亚板块绝对运动的方向一致,也平行于西南次海盆的走向。

各向异性结果与印度-欧亚板块碰撞驱动挤出模型以及古南海俯冲板块拖拽模型预期的一致。各向异性结果似乎不支持理想的地幔柱上涌驱动模型。各向异性结果不能证实亦不能证伪“大西洋型”海底扩张模型、弧后扩张模型和板缘破裂模型。由于海盆各向异性观测特别有限,后续还需要更多的观测结果来证实或证伪上述模型。

4.2 展望

南海海盆上地幔各向异性的研究存在各方面困难。一方面,现有各向异性观测稀疏,导致横向和纵向分辨率都不高,还难以对南海构造动力学的各种模型有力证伪。因而后续还需要更多的地震观测,尤其是来自海盆的。所以未来应继续加强在海盆加密布设及回收大量宽频带海底地震仪。另一方面,在同一海底观测点应考虑积累长期海底地震观测数据,同时加强数据处理手段来提高数据质量。由于海底地震仪的姿态难以控制,地震分量的倾角和方位角信息存在较大的误差,会给横波分裂确定的快波极化方向带来额外的误差。另外,受海底底流的噪声影响,地震数据信噪比低,可用于横波分裂的地震事件数目比陆上稀少得多,需要更长期的观测积累更多的可用地震数据。

-

图 2 (a) 布设的海底地震仪及提供了有用的区域S波震相分裂解的20次区域地震的分布;(b) 中央海盆的地震仪分布;(c) 提供了有用的SKS震相分裂解的两次远震的分布

Figure 2. (a) The deployed ocean bottom seismometers and the distribution of regional earthquakes which provide useful regional S-wave splitting results;(b) The enlarged version of the distribution of OBSs in central basin;(c) The distribution of the two global earthquakes which provids useful SKS splitting results

图 1 南海区域构造地质、地震台站及历史地震分布图

南海的海陆过渡带位置参考Li和Song(2012),马尼拉海沟位置来自Jiang和Wang(2021);其中中南断裂和残留洋中脊的位置来自Zhao 等(2019),红河断裂带来自Yang 等 (2015)。箭头表示板块的绝对运动方向(Gripp,Gordon,2002)

Figure 1. Tectonics of South China Sea and the distributions of seismic stations as well as history seismic events

Continental Ocean Boundaryof South China Sea refers to Li and Song (2012),and the location of Manila trench is from Jiang and Wang (2021). The locations of Zhongnan fault and the remnant mid-ocean ridges are from Zhao et al (2019) and the location of Red River Fault is from Yang et al (2015). Black arrows indicate the absolute plate motions (Gripp,Gordon,2002)

图 3 (a) 利用Taup软件并采用IASP91速度模型得到的SKS,S,pS,sS和PS震相射线路径示意图;(b)文中提供有用横波分裂解的S震相的入射角度统计图

Figure 3. (a) Schematic raypaths of SKS,S,pS,sS,and PS phases obtained using the Taup package and the IASP91 velocity model (Kennett,Engdahl,1991;Crotwell et al,1999);(b) Statistical histogram of the incident angles of the S phases used in shear-wave splitting

图 4 采用切向能量最小化(左)和最小特征值最小化(右)方法对HY16台站记录的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的PKS震相进行横波分裂分析

(a)—(c)横波分裂校正前后PKS震相滤波后的地震波形、投影到快/慢轴的波形及质点振动图(由原始的椭圆状线性化)

Figure 4. Shear wave splitting analysis on the PKS phase excited by the Guatemalan coastal earthquake on November 7,2012 recorded at station HY16 using the tangential energy minimization (left) and the minimum eigenvalue minimization (right) methods

(a)−(c) The filtered seismic waveforms,waveforms projected onto the fast /slow axis and the particle motions which arelinearized from the original elliptical shape of the PKS phase before and after correcting anisotropy

图 4 采用切向能量最小化(左)和最小特征值最小化(右)方法对HY16台站记录的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的PKS震相进行横波分裂分析

(d)能量等值线图,能量被校正到最小的那个点即为最优解(星号)

Figure 4. Shear wave splitting analysis on the PKS phase excited by the Guatemalan coastal earthquake on November 7,2012 recorded at station HY16 using the tangential energy minimization (left) and the minimum eigenvalue minimization (right) methods

(d) Contours of energy and the point where the energy corrected to the minimum is the optimal solution (asterisk)

图 6 采用最小特征值最小化(左)和波形旋转互相关(右)方法分析HY08台站记录的2012年8月14日日本本州东部区域M7.7地震激发的区域S震相的横波分裂结果

(a)—(c)为横波分裂校正前后PKS震相的地震波形、投影到快慢轴的波形及质点振动图(原始的椭圆状线性化),其中右侧图采用的是质点的位移而非质点的振动速度,下同

Figure 6. The S-phases are triggered by the M7.7 earthquake in the eastern region of Honshu,Japan on August 14,2012 recorded at station HY08,and a comparison is also made between the shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (left) and the cross-correlation (right)

(a)−(c) The filtered seismic waveforms,waveforms projected onto the fast /slow axis and the particle motions which are linearized from the original elliptical shape of the PKS phase before and after correcting anisotropy,figures in the right column use displacements rather than vibration velocities of the ground,the same below

图 6 采用最小特征值最小化(左)和波形旋转互相关(右)方法分析HY08台站记录的2012年8月14日日本本州东部区域M7.7地震激发的区域S震相的横波分裂结果

(d) 等值线图,能量和相关系数分别被校正到最小和最大的那个点即为最优解

Figure 6. The S-phases are triggered by the M7.7 earthquake in the eastern region of Honshu,Japan on August 14,2012 recorded at station HY08,and a comparison is also made between the shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (left) and the cross-correlation (right)

(d) Contour maps. The point where the energy and correlation coefficient are corrected to the minimum and maximum,respectively,is the optimal solution (asterisk)

图 5 采用最小特征值最小化(a-b)和互相关横波分裂(c-e)方法分析HY17台站记录到的2012年11月7日危地马拉沿海地震激发的SKS震相得到的空解特征

(a)表示SKS震相投影到最大及最小特征值方向的波形图;(b)为最小特征值方向能量的等值线图;(c)代表N-S和E-W向地震波位移记录;(d)表示质点运动图;(e)表示互相关方法得到的快慢波相关系数等值线图,两种方法的空解特征均为等值线图沿两个候选的快轴方向呈条带状分布

Figure 5. Examples of null results obtained through shear wave splitting analysis of the SKS phase excited by the November 7,2012 Guatemalan coastal earthquake recorded at HY17 station,and a comparison of the null results,obtained using two shear wave splitting methods of the minimum eigenvalue minimization (a-b) and the cross-correlation methods (c-e)

(a) The SKS phases projected onto the directions of the maximum and minimum eigenvector;(b) The contours of the energy in the direction of the minimum eigenvector;(c) Seismic wave displacements in the N-S and E-W directions;(d) The particle motion diagram;(e) The contours of the cross-correlation coefficients between candidate fast and slow waves. Note that the common features of both methods for null results are that the contours are distributed in strips along the two candidate fast directions

图 7 HY08地震−台站对采用最小特征值最小化方法的横波分裂结果进行聚类分析实例

(a-b)为图6所示的在0.05—0.1 Hz滤波频段针对不同横波分裂时窗得到的快轴方向和分裂时间;(c-d)为针对不同滤波频段获得的最优快轴方向和分裂时间;(e-f)为0.05-0.1 Hz和不同滤波频段的聚类分析结果,其中相同颜色的解表示通过聚类分析后划分为同一类的解

Figure 7. An example of clustering analysis on shear wave splitting results obtained using the minimum eigenvalue minimization method for the earthquake-station HY08 pair

(a-b) The fast directions and splitting times obtained at different splitting windows for the frequency band of 0.05−0.1 Hz in fig. 6;(c-d) The optimum fast directions and splitting times obtained at different filtering frequency bands;(e-f) The corresponding clustering analysis results for the frequency band of 0.05−0.1 Hz and for different frequency bands,where solutions with the same color represent solutions that are classified into the same class after clustering analysis

图 10 南海海盆及周边横波分裂及P波各向异性结果比较

黄色双箭头表示本研究得到的SKS分裂解;蓝色和蓝绿色双箭头分别为采用互相关方法和最小特征值最小化方法针对区域地震激发的S震相得到的横波分裂解;针对SKS震相在不同台站获得单个分裂解以及台站叠加解来自文献(Bai et al,2009; Hammond et al,2010;Huang et al,2011;Xue et al,2013;Yu et al,2018;Song et al,2021);P波各向异性结果来自Huang等(2015),其走向和长短分别代表快波的极化方向和各向异性的强度。台站东南方位马鲁古海区域根据横波分裂结果预期的该区域的地幔对流模型:黑色渐变粗实线代表Singihe板块下方与海沟平行的地幔流,板块两侧则是与板缘有关的偏转流,红色渐变粗实线则代表地幔楔里的角流,箭头指向流动方向

Figure 10. Comparisons of shear wave splitting results from this study with previous ones as well as the P-wave anisotropy results in the South China Sea Basin and its surrounding areas

The yellow double arrows represent the SKS splits obtained in this study;the blue and blue-green double arrows represent the splits obtained using the cross correlation method and the minimum eigenvalue minimization method for the S-phase excited by regional earthquakes,respectively;the individual SKS splits and stacked SKS splits are from previous studies (Bai et al,2009;Hammond et al,2010;Huang et al,2011;Xue et al,2013;Yu et al,2018;Song et al,2021);the P-wave anisotropy at different depths are from Huang et al (2015),and the direction and length of the short solid lines represent fast directions and anisotropic intensities respectively. The mantle convection model of the Molucca Sea region in the southeast of the OBSs consistent with most shear wave splitting results obtained in this study: the black gradient thick solid lines represent the trench-parallel flow under the Sangihe plate and the deflection flow related to the plate edge is on both sides of the plate,and the red gradient thick solid line represents the corner flow in the mantle wedge,and the arrows indicate the flow directions

图 9 南海周边区域地震的S震相分裂结果

蓝色短实线和蓝绿色短实线分别代表采用互相关方法和最小特征值最小化方法得到的横波分裂解

Figure 9. The S-wave splitting results for regional earthquakes surrounding the South China Sea

Blue solid lines and light blue solid lines represent splitting results obtained by the cross-correlation method and the smallest eigenvalue minimization method,respectively. The lengths of the lines are proportional to their splitting time,as shown in the lower left corner of the figure

表 1 提供有用数据的OBS信息

Table 1 The information of OBSs used

台站 东经/° 北纬/° 水深/m 记录起止日期 钟漂/s 水平分量方位角/° 倾斜/° 倾斜方向/° (年-月-日—年-月-日) HY02 116.306 1 16.203 3 3 750 2012-04-21—2012-12-03 86.53 20 3.5 160 HY08 117.796 5 13.800 4 4 104 2012-04-22—2012-08-19 0 218 0.7 285 HY10 116.998 3 14.598 9 4 276 2012-04-23—2012-12-09 193.2 166 0.8 215 HY15 117.537 0 16.503 3 3 753 2012-04-25—2012-12-19 0.74 154 16.3 5 HY16 118.213 4 16.451 3 3 920 2012-04-25—2012-12-13 −0.51 26 0.3 91 HY17 118.803 7 16.201 0 3 870 2012-04-25—2012-12-10 −10.54 330 2.0 131 B04 117.011 0 14.024 3 4 246 2014-07-11—2014-11-23 0 185 6.5 280 B19 116.499 0 14.500 6 4 301 2014-07-11—2014-11-23 0 350 6.5 110 B32 117.999 0 14.396 5 3 859 2014-07-13—2014-11-24 0 110 0 N/A 注:台站钟漂的误差在2—3 s之间,水平分量方位角误差约为8°;倾斜指OBS的垂直分量偏离垂向的角度(刘晨光等,2014; Le et al,2018 ;Hung et al,2021 )表 2 挑选后可用于横波分裂的地震事件信息

Table 2 The information of selected events used for shear wave splitting

事件序号 年-月-日 儒略日 发震时刻 纬度 经度 震源深度/km MW 注释 1 2012-08-27 240 043719.43 12.139°N 88.590°W 28.0 7.3 远震 2 2012-11-07 312 163546.69 13.963°N 91.854°W 24.0 7.4 远震 3 2012-04-29 120 015751.90 3.059°S 136.109°E 18.4 5.2 区域震 4 2012-05-23 144 150225.31 41.335°N 142.082°E 46.0 5.9 区域震 5 2012-06-01 153 065620.24 0.720°S 133.269°E 25.0 5.8 区域震 6 2012-06-29 181 210733.86 43.433°N 84.700°E 18.0 6.3 区域震 7 2012-07-16 198 163310.08 1.296°S 137.053°E 13.1 5.6 区域震 8 2012-07-25 207 002745.26 2.707°N 96.045°E 22.0 6.4 区域震 9 2012-08-12 225 104706.45 35.661°N 82.518°E 13.0 6.2 区域震 10 2012-08-14 227 025938.46 49.800°N 145.064°E 583.2 7.7 区域震 11 2012-09-03 247 182305.23 10.708°S 113.931°E 14.0 6.1 区域震 12 2012-09-07 251 031942.53 27.575°N 103.983°E 10.0 5.5 区域震 13 2012-10-08 282 114331.42 4.472°S 129.129°E 10.0 6.1 区域震 14 2012-10-17 291 044230.40 4.232°N 124.520°E 32.6 6.0 区域震 15 2012-11-27 332 025906.52 2.952°S 129.219°E 11.2 5.7 区域震 16 2014-07-11 192 192200.82 37.005°N 142.452°E 20.0 6.5 区域震 17 2014-07-20 201 183247.79 44.642°N 148.784°E 61.0 6.2 区域震 18 2014-08-03 215 083013.57 27.189°N 103.409°E 12.0 6.2 区域震 19 2014-08-06 218 114522.68 7.274°S 128.036°E 10.0 6.2 区域震 20 2014-09-10 253 051653.21 18.400°N 125.125°E 30.0 5.9 区域震 21 2014-09-17 260 061445.41 13.764°N 144.429°E 130.0 6.7 区域震 22 2014-11-18 322 044716.63 1.869°N 126.475°E 30.0 5.8 区域震 表 3 远震的横波分裂结果

Table 3 The shear-wave splitting results for teleseismic earthquakes

台站 事件 后方位角/° 震中距/° 震相 ϕ/° δt/s 方法 HY02 1 46.2 142.6 SKKS 46.2;−43.8 空解 切向能量 46.2;−43.8 空解 最小特征值 46.2;−43.8 空解 互相关 HY10 2 46.5 139.7 PKS 46.5;−43.5 空解 切向能量 46.5;−43.5 空解 最小特征值 46.5;−43.5 空解 互相关 HY15 2 45.5 138.1 SKKS 45.5;−44.5 空解 切向能量 45.5;−44.5 空解 最小特征值 45.5;−44.5 空解 互相关 PKS 45.5;−44.5 空解 切向能量 45.5;−44.5 空解 最小特征值 45.5;−44.5 空解 互相关 HY16 2 46.2 137.6 PKS 35±1.5 2.6±0.35 切向能量 33±6.5 2.25±0.55 最小特征值 46.2;−43.8 空解 互相关 SKKS 46.2;−43.8 空解 切向能量 46.2;−43.8 空解 最小特征值 46.2;−43.8 空解 互相关 HY17 2 47.1 137.3 SKS 47.1;−42.9 空解 切向能量 空解 最小特征值 空解 互相关 空解 切向能量 PKS 47.1;−42.9 空解 最小特征值 空解 互相关 表 4 区域性地震的横波分裂结果

Table 4 The shear-wave splitting results obtained for regional earthquakes

台站 事件 后方位角/° 震中距/° 震相 (φ±σφ)/° (δt±σδt)/s 方法 HY02 6 321.9 38.2 S,pS,sS −42±17.0 9.75±0.96 互相关 9 309.2 35.8 S,pS,sS,PS 28±4.5 2.8±0.4 最小特征值 11 185.2 26.8 S,pS,sS −47±13.0 0.75±0.23 最小特征值 −48±24.0 0.75±0.60 互相关 12 316.8 16.1 S,sS,Sn,SS −1±8.5 1.8±0.375 最小特征值 −36±25.0 0.75±0.42 互相关 HY08 3 131.4 24.7 S,pS,sS,PS −47±5 2.72±0.5 最小特征值 −11±21 1.2±0.50 互相关 4 33.0 34.6 S 50±7 2.8±0.575 最小特征值 11±22 1.15±0.39 互相关 5 132.0 21.1 S,pS,sS −34±7 1.0±0.23 最小特征值 −48;42 空解 互相关 6 322.6 41.0 S,pS,sS,PS −46±5.0 9.6±0.375 最小特征值 −49±8.0 9.85 ±0.45 互相关 7 126.7 24.3 S,pS,sS,PS 27±15.5 2.65±0.83 最小特征值 59±24.0 1.5±0.55 互相关 10 26.2 42.3 S 4±6.5 2.6±0.2 最小特征值 8±7 2.35±0.17 互相关 HY15 6 320.8 38.7 S,pS,sS,PS −38±4.5 9.6±0.28 最小特征值 −46±7.0 9.75 ±0.41 互相关 8 239.3 25.2 S,pS,sS,PS 69±9.5 6.6±1.35 最小特征值 58±6.0 7.4±0.56s 互相关 10 27.8 40.0 S 36±4.0 7.65±0.35 最小特征值 −42;48 空解 互相关 HY16 6 320.4 39.1 S,pS,sS −64±4.0 8.85±0.25 最小特征值 −63±3.0 9.0 ±0.14 互相关 11 189.2 27.3 S,pS,sS,PS −79±4.5 2.85±0.7 最小特征值 −69±2 4.65±0.24 互相关 13 151.6 23.4 S,pS,sS,PS 20±9.5 1.9±0.275 最小特征值 17±18 1.75±0.27 互相关 14 152.3 13.6 S,Sn 14±1.5 2.2±0.2 最小特征值 −67;23 空解 互相关 15 149.6 22.1 S,pS,sS,PS 42±5.0 3.25±0.85 最小特征值 54±3.0 4.9±0.43 互相关 HY17 6 320.2 39.8 S,pS,sS,PS −44±5.0 8.80±0.23 最小特征值 −45±5.0 8.95 ±0.22 互相关 B04 16 40.2 32.2 S,pS,sS,PS −67±9.0 3.55±0.775 最小特征值 −80±11 4.25±0.65 互相关 22 141.4 15.3 S,Sn,sS −79±20 2.05±0.61 互相关 B19 17 35.8 40.6 S,pS,sS,PS −34±5.5 3.1±0.15 最小特征值 18 318.0 17.6 S,Sn,sS,SS −7±2.0 3.65±0.3 最小特征值 19 151.4 24.5 S,pS,sS,PS −41±1.5 8.95±0.25 最小特征值 −41±2 9.1±0.18 互相关 20 148.9 16.9 S,Sn,sS,SS −36±3 8.05±1.0 最小特征值 −41;49 空解 互相关 21 88.1 27.1 S,sS 5±3.5 4.1±0.325 最小特征值 −12±9.0 4.85±0.35 互相关 B32 17 34.7 39.9 S,sS −26±2.0 3.65±0.2 最小特征值 19 154.5 23.7 S,pS,sS,PS −75±2.5 3.7±0.4 最小特征值 −75;15 空解 21 88.1 25.6 S,sS 7±5 2.95±0.2 最小特征值 2±10 2.95±0.4 -

陈立,薛梅,Phon L K,杨挺. 2012. 南海瑞雷面波群速度层析成像及其地球动力学意义[J]. 地震学报,34(6):754–772. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.0253-3782.2012.06.003 Chen L,Xue M,Phon L K,Yang T. 2012. Group velocity tomography of Rayleigh waves in South China Sea and its geodynamic implications[J]. Acta Seismologica Sinica,34(6):754–772 (in Chinese).

李家彪,金翔龙,高金耀. 2002. 南海东部海盆晚期扩张的构造地貌研究[J]. 中国科学:D辑,32(3):239–249. Li J B,Jin X L,Gao J Y. 2002. A study on the tectonic geomorphology of the late expansion of the Eastern sub-basin of South China Sea[J]. Science in China:Series D,32(3):239–249 (in Chinese).

李家彪,金翔龙,阮爱国,吴世敏,吴自银,刘建华. 2004. 马尼拉海沟增生楔中段的挤入构造[J]. 科学通报,49(10):1000–1008. Li J B,Jin X L,Ruan A G,Wu S M,Wu Z Y,Liu J H. 2004. Intrusion structures in the middle of the accretionary wedge of the Manila Trench[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin,49(10):1000–1008 (in Chinese).

李琳. 2016. 利用OBS数据反演南海海盆的各向异性结构[D]. 上海: 同济大学: 68. Li L. 2016. The Anisotropic Structure of South China Sea Constrained by OBS Data Geophysics[D]. Shanghai: Tongji University: 68 (in Chinese).

李思田,林畅松,张启明,杨士恭,吴培康. 1998. 南海北部大陆边缘盆地幕式裂陷的动力过程及10Ma以来的构造事件[J]. 科学通报,43(8):797–810. Li S T,Lin C S,Zhang Q M,Yang S G,Wu P K. 1998. Dynamic process of episodic rifting in the northern continental margin basin of the South China Sea and tectonic events since 10 Ma[J]. Science Bulletin,43(8):797–810 (in Chinese).

刘晨光,华清峰,裴彦良,杨挺,夏少红,薛梅,黎伯孟,霍达,刘芳,黄海波. 2014. 南海海底天然地震台阵观测实验及其数据质量分析[J]. 科学通报,59(16):1542–1552. Liu C G,Hua Q F,Pei Y L,Yang T,Xia S H,Xue M,Le B M,Huo D,Liu F,Huang H B. 2014. Passive-source ocean bottom seismograph (OBS) array experiment in South China Sea and data quality analyses[J]. Chinese Science Bull,59(16):1542–1552 (in Chinese).

任建业,李思田. 2000. 西太平洋边缘海盆地的扩张过程和动力学背景[J]. 地学前缘,7(3):203–213. Ren J Y,Li S T. 2000. Spreading and dynamic setting of marginal basins of the western Pacific[J]. Earth Science Frontiers,7(3):203–213 (in Chinese).

谢建华,夏斌,张宴华,王喜臣. 2005. 南海形成演化探究[J]. 海洋科学进展,23(2):212–218. Xie J H,Xia B,Zhang Y H,Wang X C. 2005. Study on formation and evolution of the South China Sea[J]. Advances in Marine Science,23(2):212–218 (in Chinese).

胥颐,李志伟,郝天珧,刘建华,刘劲松. 2007. 南海东北部及其邻近地区的Pn波速度结构与各向异性[J]. 地球物理学报,50(5):1473–1479. Xu Y,Li Z W,Hao T Y,Liu J H,Liu J S. 2007. Pn wave velocity and anisotropy in the northeastern South China Sea and adjacent region[J]. Chinese Journal of Geophysics,50(5):1473–1479 (in Chinese).

薛梅. 2008. 横波分裂方法研究[C]//中国地球物理学会第二十四届年会. 北京: 中国大地出版社: 390. Xue M. 2008. Study on shear-wave splitting [C]//The 24th Annual Meeting of the Chinese Geophysical Society. Beijing: China Land Press: 390 (in Chinese).

鄢全树,石学法. 2007. 海南地幔柱与南海形成演化[J]. 高校地质学报,13(2):311–322. Yan Q S,Shi X F. 2007. Hainan mantle plume and the formation and evolution of the South China Sea[J]. Geological Journal of China Universities,13(2):311–322 (in Chinese).

张健,熊亮萍,汪集旸. 2001. 南海深部地球动力学特征及其演化机制[J]. 地球物理学报,44(5):602–610. Zhang J,Xiong L P,Wang J Y. 2001. Characteristics and mechanism of geodynamic evolution of the South China Sea[J]. Chinese Journal of Geophysics,44(5):602–610 (in Chinese).

张亮. 2012. 南海构造演化模式及其数值模拟[D]. 青岛: 中国科学院研究生院(海洋研究所):1−185. Zhang L. 2012. Tectonic Evolution of South China Sea and A Numerical Modeling[D].Qingdao: Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Institute of Oceanography):1−185 (in Chinese).

钟广见,林珍,高红芳,金华峰. 2006. 南海南北缘的构造特征对比[J]. 南海地质研究,(1):30–40. Zhong G J,Lin Z,Gao H F,Jin H F. 2006. Comparison of the tectonic characteristic between north margin and south margin of the South China Sea[J]. Geological Research of South China Sea,(1):30–40 (in Chinese).

周蒂,陈汉宗,吴世敏,俞何兴. 2002. 南海的右行陆缘裂解成因[J]. 地质学报,76(2):180–190. Zhou D,Chen H Z,Wu S M,Yu H X. 2002. Opening of the South China Sea by dextral splitting of the East Asian continental margin[J]. Acta Geologica Sinica,76(2):180–190 (in Chinese).

Bai L,Iidaka T,Kawakatsu H,Morita Y,Dzung N Q. 2009. Upper mantle anisotropy beneath Indochina block and adjacent regions from shear-wave splitting analysis of Vietnam broadband seismograph array data[J]. Phys Earth Planet Inter,176(1/2):33–43.

Bell S W,Forsyth D W,Ruan Y Y. 2015. Removing noise from the vertical component records of ocean-bottom seismometers:Results from year one of the cascadia initiative[J]. Bull Seismol Soc Am,105(1):300–313. doi: 10.1785/0120140054

Ben-Avraham Z,Uyeda S. 1973. The evolution of the China Basin and the mesozoic paleogeography of Borneo[J]. Earth Planet Sci Lett,18(2):365–376. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(73)90077-0

Bowman J R,Ando M. 1987. Shear-wave splitting in the upper-mantle wedge above the Tonga subduction zone[J]. Geophys J Roy Astron Soc,88(1):25–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.1987.tb01367.x

Briais A,Patriat P,Tapponnier P. 1993. Updated interpretation of magnetic anomalies and seafloor spreading stages in the South China Sea:Implications for the tertiary tectonics of Southeast Asia[J]. J Geophys Res:Solid Earth,98(B4):6299–6328. doi: 10.1029/92JB02280

Cao L M,He X B,Zhao L,Lü C C,Hao T Y,Zhao M H,Qiu X L. 2021. Mantle flow patterns beneath the junction of multiple subduction systems between the Pacific and Tethys Domains,SE Asia:Constraints from SKS-wave splitting measurements[J]. Geochem Geophys Geosyst,22(9):e2021GC009700.

Chevrot S. 2000. Multichannel analysis of shear wave splitting[J]. J Geophys Res:Solid Earth,105(B9):21579–21590. doi: 10.1029/2000JB900199

Clift P,Lee G H,Anh Duc N,Barckhausen U,Van Long H,Zhen S. 2008. Seismic reflection evidence for a Dangerous Grounds miniplate:No extrusion origin for the South China Sea[J]. Tectonics,27(3):TC3008.

Crampin S,Gao Y. 2006. A review of techniques for measuring shear-wave splitting above small earthquakes[J]. Phys Earth Planet Inter,159(1/2):1–14.

Crotwell H P,Owens T J,Ritsema J. 1999. The Taup ToolKit:Flexible seismic travel-time and ray-path utilities[J]. Seismo Res Lett,70(2):154–160. doi: 10.1785/gssrl.70.2.154

Di Leo J F,Wookey J,Hammond J O S,Kendall J M,Kaneshima S,Inoue H,Yamashina T,Harjadi P. 2012a. Mantle flow in regions of complex tectonics:Insights from Indonesia[J]. Geochem Geophys Geosyst,13(12):Q12008.

Di Leo J F,Wookey J,Hammond J O S,Kendall J M,Kaneshima S,Inoue H,Yamashina T,Harjadi P. 2012b. Deformation and mantle flow beneath the Sangihe subduction zone from seismic anisotropy[J]. Phys Earth Planet Inter,194-195:38–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pepi.2012.01.008

Dziewonski A M,Chou T A,Woodhouse J H. 1981. Determination of earthquake source parameters from waveform data for studies of global and regional seismicity[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth,86(B4):2825–2852. doi: 10.1029/JB086iB04p02825

Eakin C M,Long M D,Scire A,Beck S L,Wagner L S,Zandt G,Tavera H. 2016. Internal deformation of the subducted Nazca slab inferred from seismic anisotropy[J]. Nat Geosci,9(1):56–59. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2592

England P,Houseman G. 1986. Finite strain calculations of continental deformation 2:Comparison with the India-Asia collision zone[J]. J Geophys Res:Solid Earth,91(B3):3664–3676. doi: 10.1029/JB091iB03p03664

England P,Molnar P. 1990. Right-lateral shear and rotation as the explanation for strike-slip faulting in eastern Tibet[J]. Nature,344(6262):140–142. doi: 10.1038/344140a0

Gripp A E,Gordon R G. 2002. Young tracks of hotspots and current plate velocities[J]. Geophys J Int,150(2):321–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-246X.2002.01627.x

Hall R,Spakman W. 2015. Mantle structure and tectonic history of SE Asia[J]. Tectonophysics,658:14–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tecto.2015.07.003

Hammond J O S,Wookey J,Kaneshima S,Inoue H,Yamashina T,Harjadi P. 2010. Systematic variation in anisotropy beneath the mantle wedge in the Java-Sumatra subduction system from shear-wave splitting[J]. Phys Earth Planet Inter,178(3/4):189–201.

Holtzman B K,Kohlstedt D L,Zimmerman M E,Heidelbach F,Hiraga T,Hustoft J. 2003. Melt segregation and strain partitioning:Implications for seismic anisotropy and mantle flow[J]. Science,301(5637):1227–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1087132

Huang Z C,Wang L S,Zhao D P,Mi N,Xu M J. 2011. Seismic anisotropy and mantle dynamics beneath China[J]. Earth Planet Sci Lett,306(1/2):105–117.

Huang Z C,Zhao D P,Wang L S. 2015. P wave tomography and anisotropy beneath Southeast Asia:Insight into mantle dynamics[J]. J Geophys Res:Solid Earth,120(7):5154–5174. doi: 10.1002/2015JB012098

Huang C Y,Wang P X,Yu M M,You C F,Liu C S,Zhao X X,Shao L,Zhong G F,Yumul G P Jr. 2019. Potential role of strike-slip faults in opening up the South China Sea[J]. Natl Sci Rev,6(5):891–901. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwz119

Hung T D,Yang T,Le B M,Yu Y Q. 2019. Effects of failure of the ocean-bottom seismograph leveling system on receiver function analysis[J]. Seismol Res Lett,90(3):1191–1199. doi: 10.1785/0220180276

Hung T D,Yang T,Le B M,Yu Y Q,Xue M,Liu B H,Liu C G,Wang J,Pan M H,Huong P T,Liu F,Morgan J P. 2021. Crustal structure across the extinct mid-ocean ridge in South China Sea from OBS receiver functions:Insights into the spreading rate and magma supply prior to the ridge cessation[J]. Geophys Res Lett,48(3):e2020GL089755.

Jiang X,Wang Z C. 2021. A critical review of existing models for the origin of the South China Sea and a new proposed model[J]. J Asian Earth Sci:X,6:100065.

Karig D E. 1971. Origin and development of marginal basins in the Western Pacific[J]. J Geophys Res,76(11):2542–2561. doi: 10.1029/JB076i011p02542

Kennett B L N,Engdahl E R. 1991. Traveltimes for global earthquake location and phase identification[J]. Geophys J Int,105(2):429–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.1991.tb06724.x

Kuo B Y,Chen C C,Shin T C. 1994. Split S waveforms observed in northern Taiwan:Implications for crustal anisotropy[J]. Geophys Res Lett,21(14):1491–1494. doi: 10.1029/94GL01254

Le B M,Yang T,Chen Y J,Yao H J. 2018. Correction of OBS clock errors using Scholte waves retrieved from cross-correlating hydrophone recordings[J]. Geophys J Int,212(2):891–899. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggx449

Li C F,Song T R. 2012. Magnetic recording of the Cenozoic oceanic crustal accretion and evolution of the South China Sea basin[J]. China Science Bulletin,57(24):3165–3181. doi: 10.1007/s11434-012-5063-9

Li L, Xue M, Yang T, Liu C, Hua Q, Le B M, Xia S, Huang H, Pan M, Huo D. 2016. A comparison of various methods of determining the horizontal orientation of Ocean Bottom Seismometers (OBS): Applying to South China Sea OBS data[C]//AGU Fall Meeting. San Francisco: American Geophysical Union: 2016AGUFMOS51C2090L

Long M D,Silver P G. 2008. The subduction zone flow field from seismic anisotropy:A global view[J]. Science,319(5861):315–318. doi: 10.1126/science.1150809

Long M D,Becker T W. 2010. Mantle dynamics and seismic anisotropy[J]. Earth Planet Sci Lett,297(3-4):341–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jpgl.2010.06.036

Mainprice D,Tommasi A,Couvy H,Cordier P,Frost D J. 2005. Pressure sensitivity of olivine slip systems and seismic anisotropy of Earth’s upper mantle[J]. Nature,433(7027):731–733. doi: 10.1038/nature03266

Miyashiro A. 1986. Hot regions and the origin of marginal basins in the western Pacific[J]. Tectonophysics,122(3/4):195–216.

Morley C K. 2002. A tectonic model for the Tertiary evolution of strike–slip faults and rift basins in SE Asia[J]. Tectonophysics,347(4):189–215. doi: 10.1016/S0040-1951(02)00061-6

Rangin C,Klein M,Roques D,Le Pichon X,Van Trong L. 1995. The Red River fault system in the Tonkin Gulf,Vietnam[J]. Tectonophysics,243(3/4):209–222.

Savage M K. 1999. Seismic anisotropy and mantle deformation:What have we learned from shear wave splitting?[J]. Rev Geophys,37(1):65–106. doi: 10.1029/98RG02075

Shen Z K,Zhao C K,Yin A,Li Y X,Jackson D D,Fang P,Dong D N. 2000. Contemporary crustal deformation in East Asia constrained by global positioning system measurements[J]. J Geophys Res:Solid Earth,105(B3):5721–5734. doi: 10.1029/1999JB900391

Silver P G,Chan W W. 1988. Implications for continental structure and evolution from seismic anisotropy[J]. Nature,335(6185):34–39. doi: 10.1038/335034a0

Silver P G,Chan W W. 1991. Shear wave splitting and subcontinental mantle deformation[J]. J Geophys Res:Solid Earth,96(B10):16429–16454. doi: 10.1029/91JB00899

Silver P G. 1996. Seismic anisotropy beneath the continents:Probing the depths of geology[J]. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci,24:385–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.earth.24.1.385

Song W K,Yu Y Q,Gao S S,Liu K H,Fu Y F. 2021. Seismic anisotropy and mantle deformation beneath the central Sunda Plate[J]. J Geophys Res:Solid Earth,126(3):e2020JB021259.

Sun Z,Lin J,Qiu N,Jian Z M,Wang P X,Pang X,Zheng J Y,Zhu B D. 2019. The role of magmatism in the thinning and breakup of the South China Sea continental margin[J]. Natl Sci Rev,6(5):871–876. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwz116

Tapponnier P,Molnar P. 1976. Slip-line field theory and large-scale continental tectonics[J]. Nature,264(5584):319–324. doi: 10.1038/264319a0

Tapponnier P,Peltzer G,Le Dain A Y,Armijo R,Cobbold P. 1982. Propagating extrusion tectonics in Asia:New insights from simple experiments with plasticine[J]. Geology,10(12):611–616. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1982)10<611:PETIAN>2.0.CO;2

Tapponnier P, Peltzer G, Armijo R. 1986. On the mechanics of the collision between India and Asia[C]//Collision Tectonics. London: Geological Society, Special Publications, 19: 113–157.

Tapponnier P,Lacassin R,Leloup P H,Schärer U,Zhong D L,Wu H W,Liu X H,Ji S H,Zhang L S,Zhong J Y. 1990. The Ailao Shan/Red River metamorphic belt:Tertiary left-lateral shear between Indochina and South China[J]. Nature,343(6257):431–437. doi: 10.1038/343431a0

Taylor B, Hayes D E. 1983. Origin and history of the South China Sea basin[C]//The Tectonic and Geologic Evolution of Southeast Asian Seas and Islands: Part 2. Washington D C: AGU: 27: 23–56.

Teanby N A,Kendall J M,van der Baan M. 2004. Automation of shear-wave splitting measurements using cluster analysis[J]. Bull Seismol Soc Am,94(2):453–463. doi: 10.1785/0120030123

Wang C Y,Yang J M,Zhu W L,Zheng M L. 1995. Some problems in understanding basin evolution[J]. Earth Sci Front,2(3/4):29–44.

Wang L L,He X B. 2020. Seismic anisotropy in the Java-Banda and philippine subduction zones and its implications for the mantle flow system beneath the Sunda Plate[J]. Geochem Geophys Geosyst,21(4):e2019GC008658.

Wang P X,Huang C Y,Lin J,Jian Z M,Sun Z,Zhao M H. 2019. The South China Sea is not a mini-Atlantic:Plate-edge rifting vs intra-plate rifting[J]. Natl Sci Rev,6(5):902–913. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwz135

Wu J,Suppe J. 2018. Proto-South China Sea plate tectonics using subducted slab constraints from tomography[J]. J Earth Sci,29(6):1304–1318. doi: 10.1007/s12583-017-0813-x

Xue M,Allen R. 2005. Asthenospheric channeling of the Icelandic upwelling:Evidence from seismic anisotropy[J]. Earth Planet Sci Lett,235(1/2):167–182.

Xue M,Le K P,Yang T. 2013. Seismic anisotropy surrounding South China Sea and its geodynamic implications[J]. Mar Geophys Res,34(3/4):407–429.

Yang T,Liu F,Harmon N,Le K P,Gu S Y,Xue M. 2015. Lithospheric structure beneath Indochina block from Rayleigh wave phase velocity tomography[J]. Geophys J Int,200(3):1582–1595. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggu488

Yu Y Q,Gao S S,Liu K H,Yang T,Xue M,Le K P,Gao J Y. 2018. Characteristics of the mantle flow system beneath the Indochina Peninsula revealed by teleseismic shear wave splitting analysis[J]. Geochem Geophys Geosyst,19(5):1519–1532. doi: 10.1029/2018GC007474

Zhao M H,Sibuet J C,Wu J. 2019. Intermingled fates of the South China Sea and Philippine Sea plate[J]. Natl Sci Rev,6(5):886–890. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwz107

下载:

下载: